An Attempt to Organize

Thinking Patterns Using

"Kobo-chan" as an Example

(3) Deduction and Induction

Contents

◆ Examples of Deduction

Following An Attempt to Organize Thinking Patterns Using Kobo-chan as an Example (2) Analogy, I will explain ‘deduction and induction’ using Kobo-chan as an example.

I was going to explain induction, but I couldn’t find any examples that could be called pure induction. However, there were a few examples of deduction after induction so I will explain deduction first.

For example, we can say that A is an example of deduction.

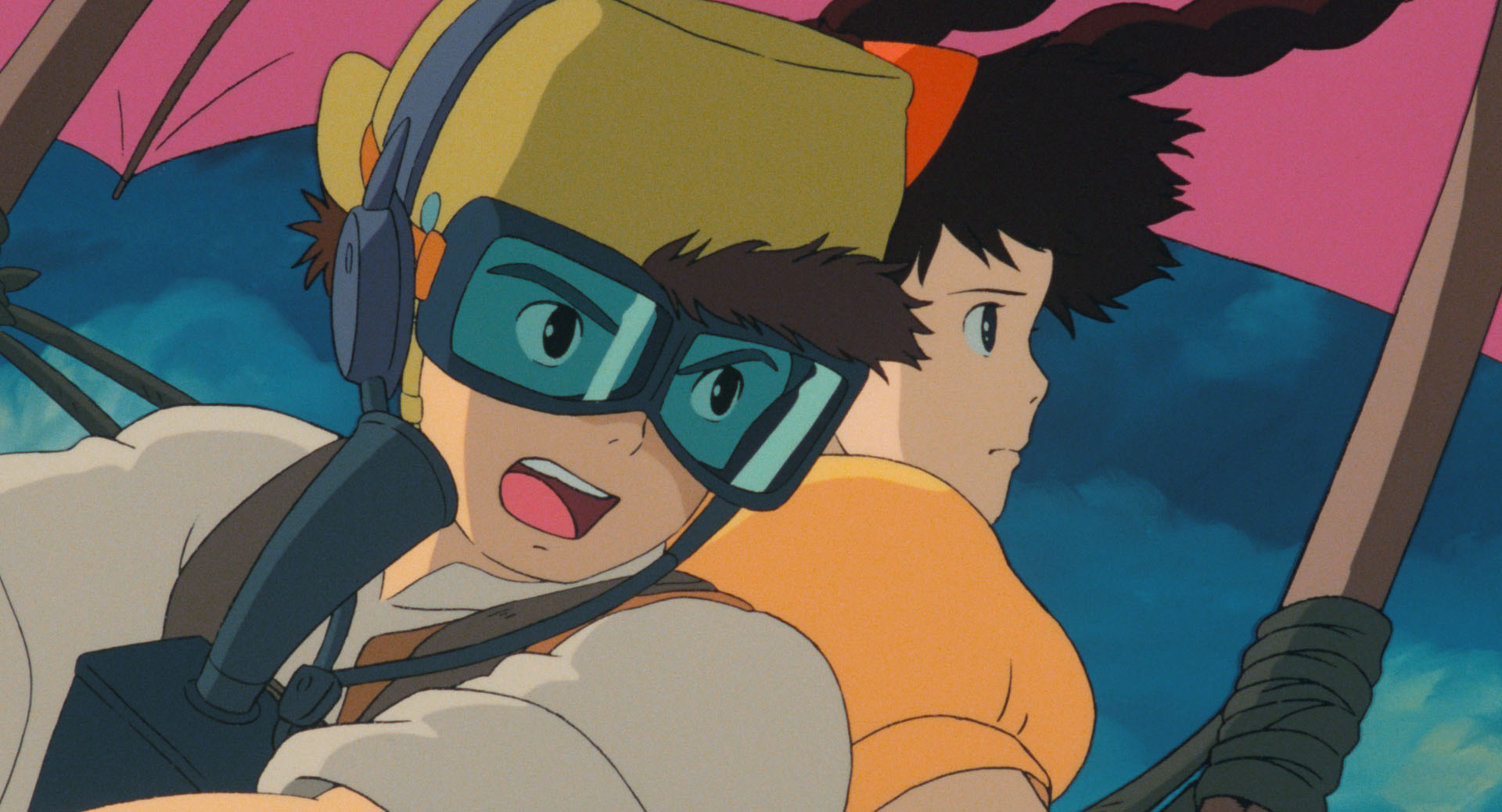

A

From Kobo-chan Masashi Ueda/Sōyō-sya

©UEDA Masashi

Here’s a list of the thought process Kobo-chan is going through:

Dried food returns to its original state when it is put in water.

Niboshi is dried food.

Therefore, if I put Nibosh in water, it will return to its original state. (It comes back to life.)

This is precisely what is characteristic of deduction, the ‘syllogism.’ In the syllogism, the characteristics of a set are first described. In this case, the mother talks about the set ‘dried things’ characteristic that ‘returns to its original state when put in water.’

When Kobo-chan heard this, he thought that “niboshi” is also a dried product. Kobo-chan thought that niboshi was an element that belonged to the set of ‘dried things.’ And since niboshi is also dried, he thought that if he put it in water, it would return to its original state, which he did.

Kobo-chan seems to be interpreting the statement “return to original” to mean “come back to life.” I can feel the nuance of his expectation that the niboshi in the water will return to life and start swimming.

But in reality, niboshi are boiled before they are dried. (Niboshi is dried anchovies that have been boiled and then dried.) Therefore, when you put them in water, they may soften up a little, but they will not return to their original form, and of course, they will not return to life.

The reason why Kobo-chan’s deductive conclusion was wrong was that:

・Dried food returns to its original state when it is put in water.

・Niboshi is dried food.

This is because the second of the two premises were wrong.

A deduction can only produce a correct conclusion when the two premises are correct.

B is another example of deduction regarding dried food.

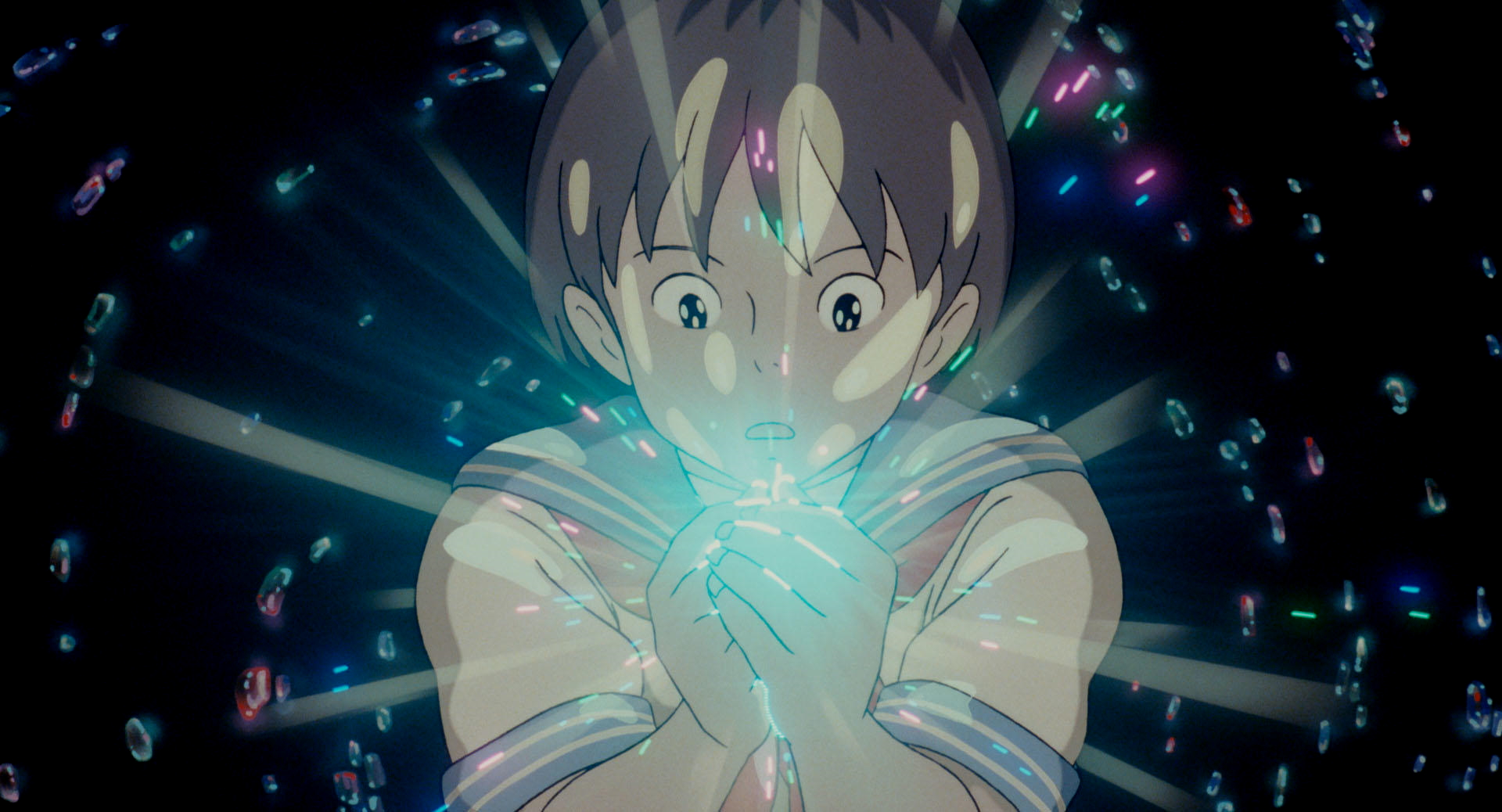

B

From Kobo-chan Masashi Ueda/Sōyō-sya

©UEDA Masashi

The thought process that Kobo-chan is going through can be expressed in a syllogism:

The dried thing gives off umami.

Laundry is something that is dried.

Therefore, laundry gives off umami.

This is a proper deduction.

Which of the two premises was wrong this time was the first one, ‘dried thing gives off umami.’ Here, ‘dried thing’ was limited to edible food, but Kobo-chan expanded it to include more than just-food.

It seems that it is quite difficult to reach a correct conclusion by deduction.

◆ From Induction to Deduction

How about the next C?

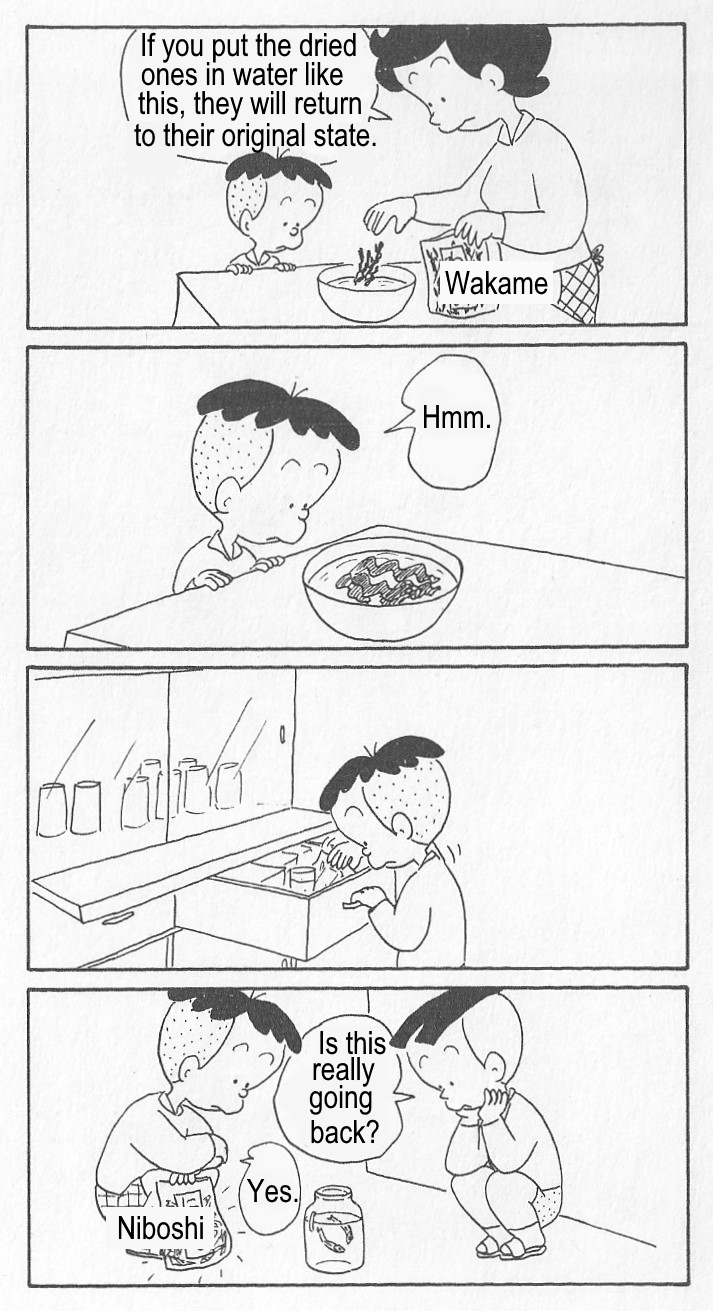

C

From Kobo-chan Masashi Ueda/Sōyō-sya

©UEDA Masashi

Again, Kobo-chan must be making deductions. The process is:

Moldy food should be thrown away.

This cheese is a moldy food.

Therefore, this cheese should be thrown away.

However, asking Kobo-chan how he got the first premise, “moldy food should be thrown away,” he got it exactly by induction.

Before finding the blue cheese in the refrigerator, Kobo-chan watched his grandmother and mother each find moldy food and probably throw it away. This may have given him one insight that moldy food should be thrown away. Here’s the process:

We can’t eat a moldy bun, so we throw it away.

We can’t eat moldy bread, so we throw it away.

Both buns and bread are food.

Therefore, moldy food cannot be eaten, so we throw it away.

Kobo-chan thought that the properties that apply to the buns and bread would also apply to the whole set to which the buns and bread belong. This is just induction.

In deduction, we first have knowledge of the set as a whole, and then we apply the properties to the elements that belong to the set. On the other hand, induction infers that properties that apply to individual elements in common will also apply to the entire set to which they belong.

Deduction: assumes that what is true of a set is also true of its elements.

Induction: assumes that what is true of elements is also true of a set.

So it’s just the opposite for ‘set’ and ‘element.’

In I and II, the knowledge that Kobo-chan uses as a premise for deduction was given to him by others. In III, however, Kobo-chan’s knowledge as the premise for his deduction was obtained by himself. And it is obtained by induction. So, in this case, Kobo-chan’s knowledge as a premise for deduction was obtained through induction.

How about the next D?

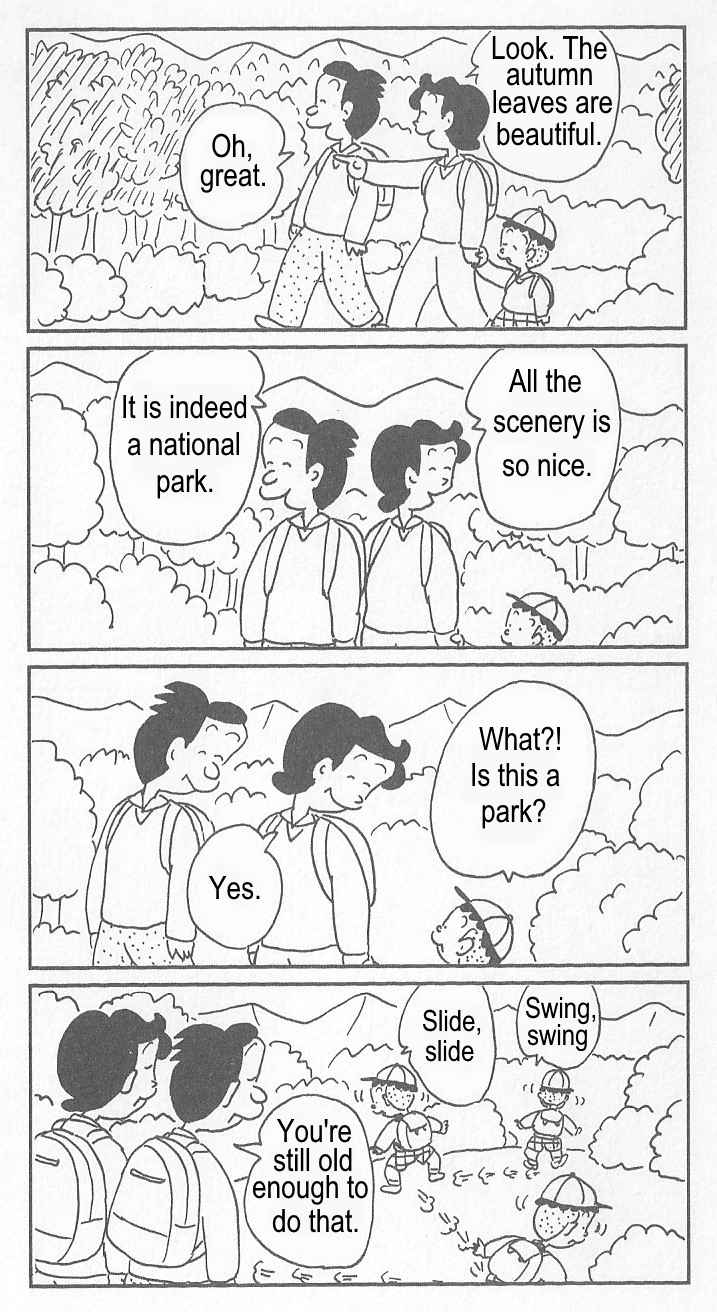

D

From Kobo-chan Masashi Ueda/Sōyō-sya

©UEDA Masashi

Let’s try to express Kobo-chan’s thinking in a syllogism:

Parks have playground equipment.

A national park is a park.

Therefore, national parks have playground equipment.

It’s a neat syllogism, but the conclusion Kobo-chan draws is incorrect. The first of the two premises, “parks have playground equipment,” is wrong. And the first premise was not given to Kobo-chan by anyone, but probably by his own experience. For example:

X park has playground equipment.

Y park also has playground equipment.

Z park also has playground equipment.

X park, Y park, and Z park are all parks.

Therefore, parks have playground equipment.

This is what he seems to have gotten from the process. He thinks that what is true for each park that Kobo-chan knows will be true for the park as a whole. This is precisely induction. And the knowledge obtained by induction is now used as a premise for the deduction. In D, only the process of deduction is depicted, but it implies that the knowledge on which the deduction is based has been obtained in advance by induction.

◆ Useful and troublesome

The advantage of this deduction and induction is that it eliminates the need to thoroughly examine a thing’s properties. For example, to find out whether the statement about the set “Japanese people are serious” is correct, we need to find out whether all Japanese people are serious. But we can’t afford to do that. Deduction and induction are patterns of thought that allow us to skip those steps and make judgments about sets and elements “for the present.” In the style of Gregory Bateson, it will enable the mind to achieve economy.

We can say that this deduction and induction is the transfer of judgment between sets and elements. But it is transferred not only judgments but also simple positive and negative emotions.

For example, let’s say you become a fan of a particular member of an idol group. Then, in most cases, it seems that your fondness for that member will also transfer to your fondness for the group itself.

On the other hand, when a new player joins a sports team that you favorite, your fondness for the team will likely be transferred to the new player.

The former can be said to be inductive favoritism, while the latter can be said to be deductive favoritism.

But when favor shifts, naturally, the feeling of dislike shifts as well. In other words, a person who dislikes an element may dislike the entire set to which that element belongs. Conversely, a person who has an aversion to a certain set may dislike an element without knowing much about the individual elements.

This is a troubling phenomenon. It seems that a lot of discrimination, for example, comes from this kind of thought process. Much of the discrimination must not occur if we cannot transfer judgments and feelings between sets and elements. But on the other hand, until we have examined all the elements, that is until we have been thoroughly empirical, we cannot make any judgment about either the sets or the elements. Discrimination seems to be a side effect of the economy of the mind.

In this sense, deduction and induction are useful and troublesome and require careful “handling.”

Generally speaking, this induction and deduction are called “logical thinking.” It used to be thought that only humans could think logically, but it is now known that a wide range of organisms, including fish, can think logically. (※1) It is a thought pattern that awaits further research.

Next, I am going to explain “abduction (hypothesis formation)” using Kobo-chan as an example.

※The content, text and images are prohibited to reproduce, quote or use in any way other than for correct quotation.