An Attempt to Organize

Thinking Patterns Using

"Kobo-chan" as an Example

(4) Abduction

Contents

◆ Examples of Abduction

Following Deduction and Induction – an attempt to organize thinking patterns using “Kobo-chan” as an example (3), I will explain abduction (hypothesis formation).

For example, in the following A, we can say that the character is abducting, i.e., forming a hypothesis.

A

From Kobo-chan Masashi Ueda/Sōyō-sya

©UEDA Masashi

When Kobo’s father, Koji, returns home, he sees that a pair of boots have been taken off at the entrance. Koji then adjusts his hair and ties in the mirror. He greets his family, smiling so much that they find it puzzling. He then blushes when he realizes that the boots belong to his wife.

When he saw the boots, Koji thought that perhaps a woman, a young woman, was visiting the house as a guest. In other words, he hypothesized that the boots were there because “a young woman was a guest in the house.” He then dressed up and made himself look agreeable to this hypothetical guest. (Of course, this is only possible in Japan, where people take off their shoes in the house.)

Abduction, translated as “hypothesis formation,” is a thinking pattern first formulated by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. According to “Abduction: The Logic of Hypothesis and Discoveryアブダクション 仮説と発見の論理” (Yuji Yonemori, Keiso Shobo), Peirce described the process as:

A surprising fact C is observed.

But if H were true, then C would be a matter of course.

Thus, there is reason to believe that H is true.

Yonemori simplifies this as follows:

There is an amazing fact C.

But if H, then C.

Therefore, it is H.

The thought process Koji went through can be applied to this formulation as follows:

There are boots at the entrance that are not usually there.

However, if a female visitor is wearing boots, it is not surprising that there are boots at the entrance.

Therefore, a female visitor is coming.

The “surprising fact” is exaggerated here, but it is probably unusual, not routine, to find someone’s removed boots at the entrance for Koji. He created that hypothesis because he wanted a belief that would explain to himself why that unusual event occurred.

B is another example of abduction, but it does not end there.

B

From Kobo-chan Masashi Ueda/Sōyō-sya

©UEDA Masashi

Kobo-chan is playing with a paper helmet. However, his mother, Sanae, who was watching him, noticed that Kobo’s neck was unnaturally strained. She tried to make him bow, but he would not do so. When she takes off the helmet, she finds that Kobo has hidden a Kashiwa-mochi (a rice cake wrapped in an oak leaf).

Photo of Kashiwa Mochi. In Japan, on May 5, Boy’s festival, people decorate samurai helmets and eat Kashiwa Mochi. From this, we know that this is the timing.

Sanae made Kobo-chan bow because she guessed that Kobo-chan might be hiding something on his head. In other words, she made a hypothesis that would explain why there was a strange strength in her son’s neck, and she wanted him to bow to test the truth of that hypothesis.

Sanae’s hypothetical process goes as follows:

Kobo-chan is wearing a helmet, and his neck is unnaturally strained.

However, if Kobo-chan is hiding something in his helmet, his neck is natural to be unnaturally strained.

Therefore, Kobo-chan is hiding something in his helmet.

One could say that this B is a further example of deduction. Abduction is only the formulation of a hypothesis and does not include the process of testing its true or false. If this B had ended with Sanae thinking, ‘Kobo-chan must be hiding something in his helmet,’ it would have been a true example of abduction. But it did not end there.

To test the truth of a hypothesis, one must first consider how to know if it is correct or “true” and, conversely, how to see if it is wrong or “false.” It is not possible to determine true or false by any method. We must first consider how to accurately determine true/false. Sanae may have thought as follows:

People who have something on their heads don’t bow because they don’t want to drop it.

Kobo-chan is a person who has something on his head.

Therefore, Kobo-chan does not bow.

This is the deduction explained in An Attempt to Organize Thinking Patterns Using Kobo-chan as an Example (3) Deduction and Induction.

This provided a way to determine the truth or falsity of the hypothesis. If the hypothesis is correct, then this deduction is true; Kobo-chan would not bow; if it is incorrect, he might bow.

However, it has not yet been actually determined to be true. In other words, it has not yet been verified. To verify it, we need a method. Here, Sanae would like to have “a way to make Kobo bow.” If she waits naturally, Kobo-chan may bow sooner or later, but he may not do it forever if he hides something in his helmet. She wants to make Kobo-chan bow actively in some way.

In the end, Sanae said to Kobo-chan, “Bow!” This could have been, for example, the following thought process:

Japanese people have many opportunities to say “Bow(Rei)” and do bow.

Kobo-chan is Japanese.

Therefore, Kobo-chan does bow when he is told to do so.

As a result, Kobo-chan did not bow. This indicates that Sanae’s initial hypothesis may be correct. However, there is still no proof. There may be some other reason why Kobo-chan did not bow. Maybe he has a back injury. So she finally took off the helmet and found a Kashiwa-mochi there. That is why Kobo-chan had hidden it there. The hypothesis was proved to be correct.

The bullet points of what Sanae did are:

・Observation of the fact that Kobo-chan’s neck is strangely tense.

・Formation of a question as to why there is a strength.

・Formulate a hypothesis that Kobo-chan is hiding something on top of his head.

・Formation of a method to determine the truth of the hypothesis that Kobo-chan will not bow if the assumption is correct.

・Formation of a verification method that makes him bow.

・Verification.

・Recognition that the hypothesis may be correct from consideration of the verification results.

・Confirmation that there is something on top of his head.

To our surprise, Sanae went through these processes in an instant.

This could be described as troublesome. For example, it would have been fine if Sanae had observed the unnatural force in Kobo-chan’s neck, wondered about it, and suddenly removed his helmet. It would have been such an example if the third panel had not been there. But just by making him bow before that, we can see that so much thought has gone into this. Sanae’s insight and quick thinking as a mother were depicted in only four frames.

The following C also seems to me to be a brilliant insight.

C

From Kobo-chan Masashi Ueda/Sōyō-sya

©UEDA Masashi

His kindergarten teacher told Kobo-chan to wash his hands before eating. One day later, Kobo-chan is at home and begins to wash his hands. Sanae sees Kobo-chan washing his hands. Then, while Sanae waits where the sweets are placed, Kobo-chan comes there.

Sanae ‘observed’ Kobo-chan washing his hands and ‘wondered’ why he was cleaning at this hour. We can tell that it is halfway through the day, at least it does not seem to be before dinner, from the way Grandpa and Grandma look and that there is no food prepared on that table. (In this house, Sanae and Grandma cook meals.)

Sanae then formulates a hypothesis that answers the question. The process is as follows:

My son is washing his hands at odd hours.

However, if the son is going to eat sweets without permission, it is natural for him to wash his hands.

Therefore, the son is trying to eat sweets without permission.

First, we learn that this house seems to rule that Kobo-chan is not allowed to eat sweets without permission. Her son is trying to break that rule. It can also be said to express the funny side of the story that Kobo-chan is trying to break the family rule while obeying a rule that his kindergarten teacher told him.

Sanae not only makes a hypothesis but also tries to confirm its truth. If the hypothesis is correct, the sweets will be eaten without permission. She must think of a way to prove the truth of the idea. The thought process is as follows:

People who intend to eat sweets come where the sweets are.

Kobo-chan is a person who intends to eat sweets.

Therefore, Kobo-chan comes to the place where there are sweets.

Now she can determine the truth or falsity of the hypothesis. If the idea is correct, Kobo-chan will come to the place where the sweets are, and if it is wrong, he will not.

However, the verification method is not automatically determined once the judgment method is known. The next step is to think of a verification method and then the actual verification. In this case, it is simply a matter of waiting in front of the shelf where the sweets are kept. The thought process is as follows:

Kobo-chan comes to the place where there are sweets.

Sweets are on the shelf.

Therefore, Kobo-chan comes to the shelf.

And as Sanae waited in front of the shelf, her son came to her. The hypothesis turned out to be correct. At the same time, she could prevent the sweets from being eaten without permission.

This example also does the following:

・Observation of events

・Question formation

・Hypothesis formation

・Formation of a method to determine the truth or false of a hypothesis

・Formation of methods for verifying truth or false

・Verification

・Judging the truth or false of a hypothesis based on the results of verification

・Confirmation

Sanae conducts these processes in an instant.

This is another thing that can be troublesome. If Sanae had seen Kobo-chan washing his hands and immediately thought he would eat the sweets, she could have called out to him on the spot, “Don’t eat the sweets.” However, there may be another reason why her son started washing his hands. Maybe he would do some work that required his hands to be clean. If so, Kobo-chan would be hurt because he did not intend to eat the sweets but was warned because he suspected.

Sanae did not do so and let Kobo-chan’s actions tell themselves the truth or false of the hypothesis. Of course, it is possible that Kobo-chan came to the shelves and did not even intend to eat the sweets. However, from Kobo-chan’s fearful look, we can surmise that Sanae’s hypothesis was correct.

◆ Induction and Abduction "Amazing Fact"

Even Peirce, who proposed abduction, considered the difference between induction and abduction, and Yonemori followed suit, writing about the differences.

I have been thinking about it, and in considering the difference, how about the following story?

Mr.A works for a company, and there is a Mr.B in the same office. One day, this Mr.B suddenly started to drink protein after lunch without fail. He started drinking on Monday and then on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday.

At this point, if A thinks, “Since Mr.B has been drinking protein after lunch for four consecutive days, he will probably do the same after lunch on Friday, the fifth day,” he is making an inductive inference. To be precise, he is making a deduction from induction: if he generalizes that Mr.B drank protein four days in a row and would drink it after every lunch, this would be the inductive step. And if he then assumes that Mr.B will drink it again on Friday, the fifth day in a row, this is the deduction stage.

On the other hand, suppose that Mr.A wonders, “Why did Mr.B start taking protein in the first place?” And if he hypothesized, for example, that the reason for explaining this is that “Mr.B started bodybuilding,” this would be an abduction.

The inference that “Mr.B will probably drink protein on Friday, too.” doesn’t mean he has thought of a “reason” for taking that action, but abduction is thinking of a reason.

So, is it correct to understand that abduction is to think of “reasons”?

What would happen in the following cases?

There used to be a person named Mr.C in Mr.A’s office. One day, this Mr.C suddenly started drinking protein after every lunch. Mr.A was curious and asked Mr.C why, and he replied, “Because I started bodybuilding.”

If Mr.B then started drinking protein, and Mr.A inferred that since Mr.C once started drinking protein because he began bodybuilding, Mr.B must have started drinking it because he also started bodybuilding, would this be an abduction? Or is it induction? Or did he make an “inductive abduction”?

In this case, Mr.A is still considering the “reasons” for the actions taken by Mr.B. But at the same time, he is also generalizing. In this example, we see that Mr.A has never performed an abduction; the reason Mr.C started drinking protein is something he learned from Mr.C, not a hypothesis made by Mr.A. And seeing that Mr.B has started taking protein, he is just generalizing by induction, assuming that it is for the same reason as Mr.C. In other words, Mr.A is not performing abduction.

When we think about it this way, we eventually realize that Peirce’s writing in his formulation that “a surprising fact C is observed” was a wise move. Abduction takes place only when a “surprising fact” is observed. It can say that thinking about reasons is not necessarily abduction. In the above example, for Mr.A, who knew that Mr.C used to take protein because he started bodybuilding, the fact that Mr.B had newly formed taking the protein is not particularly surprising. (Although the real reason for Mr.B’s protein consumption may surprise Mr.A.)

What constitutes “surprising” will vary from event to event.

Here I introduce the concepts of “synchronic” and “diachronic.” In layman’s terms, what happens simultaneously is a “synchronic” event, and what happens in a sequence is a “diachronic” event. It is a synchronic event that Mr.A and Mr.B eat ramen and curry rice respectively at the same time on the same day, and if Mr.A eats bread for breakfast and udon for lunch, they are a diachronic event.

It may be surprising that some multiple facts happen in a synchronic manner, i.e., simultaneously, or it may be surprising that they do not occur. It is surprising when what we expect to happen simultaneously does not happen. On the other hand, it would be surprising if things that we expected would not happen at the same time did happen simultaneously. The same is true diachronically. We are surprised when things we expect to happen in sequence do not happen and when things we expect not to happen in series do happen.

Abduction can occur only when something “surprising” happens to the person, even if these cases vary.

◆ Number of facts

There was “one surprising fact” for each character in the examples A-C above. In other words, they each had one hypothesis that explained one event. However, the “surprising fact” does not have to be just one in abduction, and it is possible to formulate a hypothesis that can explain multiple facts simultaneously. It is here that the difference between abduction and induction becomes clear.

For example, in the case of A, Koji hypothesized that there must be a female visitor, based on the single fact that there are boots at the entrance that he does not usually see. However, let us assume, for example, that there was a toy poodle tied up in front of the house or at the entrance, which Koji had never seen before. And if he also saw the boots taken off and made the above hypothesis, it would be clear that this is abduction and not induction.

The process is written as follows:

A toy poodle, which I have never seen before, is tied up in front of the house.

In addition, an unfamiliar pair of boots are taken off at the entrance.

However, if a female visitor with a pet dog is coming to the house, it is natural that the toy poodle is tied up and the boots are taken off.

Therefore, a female visitor is coming.

The fact that “a toy poodle I’ve never seen before is tied up” and “an unfamiliar pair of boots is off at the entrance” could be two completely different events. The toy poodle tied up may have been left there by a heartless person, and the boots may be there because a female guest is visiting. But to try to explain these two facts with the same single hypothesis is not induction but clearly abduction. Because it is the “first time” Koji has seen the toy poodle. If induction is a generalization, in this case, there is not enough data in the form of experience to generalize. Conversely, induction is possible only when there is enough data and experience to generalize. There is no way to explain the fact that one encounters for the first time by generalization.

I think we can clarify the difference between abduction and induction by assuming that abduction is a thinking pattern in which one formulates a hypothesis that explains multiple facts simultaneously from the beginning. The formulation above by Pearse is not inconsistent with that formulation if that fact is one case.

In other words, we can define abduction as “thinking to formulate a hypothesis that can explain ‘n facts’ simultaneously.” Any number can be applied to that n, and the example of Kobo-chan above can be said to be a case where n is 1.

◆ Number of hypotheses Establishment of Hhybrid Vigor

After problematizing the number of facts, let’s think about the number of hypotheses.

In philosophy, there is a kind of principle called “Occam’s razor,” or “the fewer hypotheses, the better.” We can explain each fact by a different hypothesis. But if we continue to do this, as the number of facts increases, so does the number of assumptions. When there are three facts, only three hypotheses are needed, but when there are 100 facts, the number of hypotheses will also increase to 100. It is hard to develop 100 hypotheses, and we can’t remember them all. This is not a very good way to do it. And when faced with that many facts, anyone would typically start looking for a hypothesis that would successfully explain most of them. Psychologically, “fewer hypotheses are better” is also valid.

In the history of science, it seems that technological innovation often occurs when the number of hypotheses is reduced.

The establishment of “hybrid vigor” as a breeding method by American biologist George Harrison Shull, as mentioned in The “secret” relationship between Motoo Kimura and Gregory Bateson, is a perfect example.

George Harrison Shull(1874-1954)

From 90 Years Ago : The Beginning of Hybrid Maize

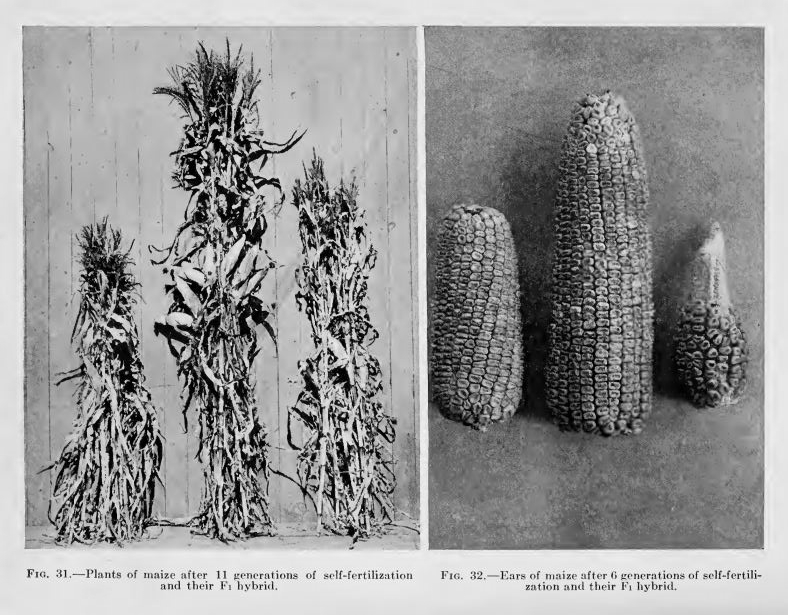

Continued artificial selection in crossbreeding crops and livestock often results in “inbreeding depression” and degradation of traits. In the past, it was believed that inbreeding depression was caused by inbreeding and self-fertilization. It was thought that some harmful factors existed, which gradually accumulated through continued self-fertilization and inbreeding, resulting in inbreeding depression. But after learning of Mendel’s laws, Shull thought that genotype, not reproductive mode, was the cause. Specifically, he thought it might be due to the increased proportion of “homozygotes” (e.g., aa) for harmful recessive genes in alleles.

At the same time, Shull realized that the genotype could also explain the “hybrid vigor” phenomenon that German botanist Kölreuter had discovered more than 100 years earlier in his work on leaf tobacco hybridization. Specifically, he thought it happens when alleles are “heterozygotes” (e.g., Aa). In other words, he realized that each phenomenon is not caused by the “quantity” of something but by the “combination” of genotypes and their “proportion” on the whole. Shull hypothesized and later demonstrated that the same principle could explain two phenomena that had been thought to be separate: inbreeding depression and hybrid vigor.

Incidentally, the term “hybrid” here refers to different “varieties” or “strains” and does not literally mean other species. And hybrid vigor is different from mere “crossbreeding.” The specific method is to first create multiple “inbred lines” by intentionally continuing self-fertilization or inbreeding. Inbred lines are those in which the alleles are almost 100% homozygotes. (For self-breeding crops, this is called a “pure line.”) And when different inbred lines are crossed, some combinations result in much larger offspring generations, higher-yielding, and more disease resistant than their parents. At the same time, their children will all be heterozygote for the same genotype, thus stabilizing quality. This is based on the knowledge of Mendel’s law, which states that if you cross individuals with genotypes AA and aa, for example, all of their offspring will be Aa. The hybrid vigor is to make the offspring generation (F1) with superior traits and uniform quality into a commodity. In this way, Shull showed that hybrid vigor could be created intentionally, not by chance, and could be a practical breeding method.

Each side is a different inbred line created by repeated self-fertilization. The middle is the F1 born between them. You can see that F1 has grown much larger and more splendid than its parents.

From Inbreeding and Outbreeding Their genetic and sociological significance by E.M.East&D.F.Jones

Incidentally, when the F1s are crossed with each other, they are genotypically crossed with Aa and Aa. This will result in a variety of genotypes, such as AA, Aa, and aa, in the offspring generation, which will lead to a variety of phenotypes. In other words, quality will vary. That is why seed companies that sell F1 seeds say that after growing F1 seeds, it is better to buy seeds every season instead of self-seeding.

The F1 turnips grown were self-seeded and their F2s are being tested to see what happens to them.

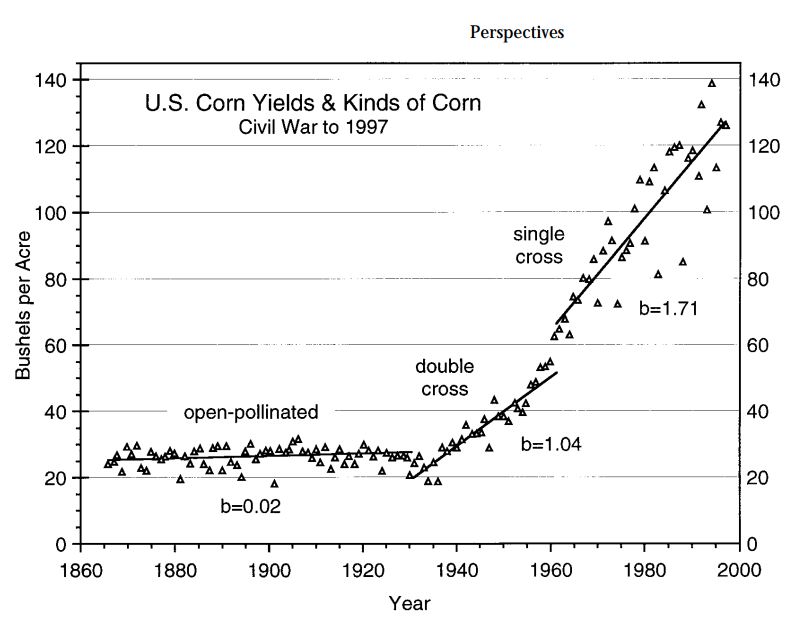

Corn yields in the U.S. were not improved for at least about 70 years, from 1865, when the Civil War ended for which data are available, until the 1930s, when hybrid vigor was introduced into the field. During that time, various studies were conducted, and several varieties were produced, but the critical factor, yield, remained the same.

For example, E. M. East, who, along with Shull, is considered a key figure in establishing hybrid vigor in corn, experimented to see if selection could increase grain protein and oil content. Indeed, he was able to grow them, and however, he also found that the yield decreased.

Of course, experiments were conducted to increase the yield itself by selection. The first few generations increased the product, but inbreeding depression occurred and did not work after that. Continuous selection from generation to generation without crossbreeding with other strains or breeds means that the same individuals or strains of the same ancestors continue to be crossbred, which is, in effect, inbreeding. For example, individual selection is the process of selecting superior individuals from a group, mating them, then selecting superior individuals again from among their offspring, and repeating the operation. In other words, in the second generation, the breeding is suddenly done between brothers and sisters, continuing after that. This is true whether the task is to select two individuals out of ten or two individuals out of 10,000. If this process is continued, inbreeding depression is almost certain to occur. Therefore, instead of selecting superior individuals, researchers hoped that inbreeding depression would not happen if they repeated the process of “mass selection,” in which multiple superior individuals are chosen to form a group and then allowed to mate within that group from generation to generation freely. However, the result was the same.

After learning about Mendel’s laws, Shull also realized that both continued selection and continued self-breeding are the same in the sense that the proportion of homozygotes increases. The degree of this increase becomes more robust with each generation, and the percentage of homozygotes increases by that much. This is why inbreeding depression occurs with continued selection.

It is now known that there is a limit to the effect of artificial selection. In population genetics and breeding, that limit is called the “selection limit” or “selection plateau.” According to Motoo Kimura, Alan Robertson’s selection limit supported population genetics is an extension of Kimura’s work on gene fixation probability.

Change in corn yield in the U.S. b is regression coefficient. Double-cross was a method devised by D. F. Jones, a student of East’s, to cross four varieties in order to obtain a large amount of parental seed. Later, when single-cross which were initially advocated by Shull, could be realized, the degree of increase in yield was seen to increase further.

From 90 Years Ago : The Beginning of Hybrid Maize

At that time, the yield of corn in the U.S. was about 1.6 tons per hectare. However, once hybrid vigor was introduced, yields continued to increase steadily, reaching nearly 9 tons per hectare in the 1990s. This is an unprecedented success in the history of breeding.

This hybrid vigor is now incorporated in various crops and livestock other than corn. Many vegetables sold in Japan are said to be produced by hybrid vigor, as are chickens and pigs. For example, in Japan, pork labeled “sangen-ton(three-crossed pig) ” or “yongen-ton(four-crossed pig)” is commonly sold. The term “sangen-ton” refers to a pig that is a crossbreed of three purebred breeds, meaning that it has undergone two generations of hybrid vigor, while “yongen-ton” refers to a pig that has experienced three generations. In other words, sangen-ton and yongen-ton are not the names of specific breeds or strains.

In China, the government is working on a national level to increase rice hybrid vigor and has succeeded in increasing production. (Rice is almost entirely self-breeding, so it takes a lot of ingenuity to achieve hybrid vigor.)

Shull hypothesized and demonstrated that two phenomena, inbreeding depression, and hybrid vigor, could be explained by a single principle. He thereby established hybrid vigor as a practical breeding method, and this breeding method is now supporting our food supply.

While the increase in hypotheses is due to abduction, the decrease in hypotheses is also due to abduction.

Animation on Shull establishing hybrid vigor in maize.

◆ Dolphin's abduction Can animals form hypotheses?

Can animals also perform abduction?

In the article “Double Bind, 1969,” included in Gregory Bateson’s Ecology of the Mind, he discusses an example of dolphins performing abduction.

Consider a very simple paradigm: a female porpoise (Steno bredanensis) is trained to accept the sound of the trainer’s whistle as a “secondary reinforcement.” The whistle is expectably followed by food, and if she later repeats what she was doing when the whistle blew, she will expectably again hear the whistle and receive food.

This porpoise is now used by the trainers to demonstrate “operant conditioning” to the public. When she enters the exhibition tank, she raises her head above surface, hears the whistle and is fed. She then raises her head again and is again reinforced. Three repetitions of this sequence is enough for the demonstration and the porpoise is then sent off-stage to wait for the next performance two hours later. She has learned some simple rules which relate her actions, the whistle, the exhibition tank, and the trainer into a pattern – a contextual structure, a set of rules for how to put the information together.

But this pattern is fitted only for a single episode in the exhibition tank. She must break that pattern to deal with the class of such episodes. There is a larger context of contexts which will put her in the wrong.

At the next performance, the trainer again wants to demonstrate “operant conditioning,” but to do this she must pick on a different piece of conspicuous behavior.

When the porpoise comes on stage, she again raises her head. But she gets no whistle. The trainer waits for the next piece of conspicuous behavior – likely a tail flap, which is a common expression of annoyance. This behavior is then reinforced and repeated.

But the tail flap was, of course, not rewarded in the third performance.

Finally the porpoise learned to deal with the context of contexts – by offering a different or new piece of conspicuous behavior whenever she came on stage.

From “Double Bind, 1969″ in Steps to an ecology of mind. Gregory Bateson.

For more information on this experiment, one can refer to Karen Pryor’s LADS before the WIND. Because Karen was the very trainer of the show that Bateson is writing about. First, an explanation of “operant conditioning” would be in order.

One major problem arises when humans attempt to train dolphins. That is that humans on land have no way to punish dolphins in the water. The same land-based animals can be punished by physically striking them, but this is difficult to do with dolphins. Electricity could be passed through the water to punish them, but waterways connect the dolphins’ tanks. Therefore, if you want to punish a dolphin in training, you will also give electric shocks to the dolphins in the other tanks. This would confuse the dolphins and make them lose faith in humans, making training impossible.

Karen’s reference there was behaviorist “operant conditioning.” In dolphin training, the dolphin is allowed to swim freely, rather than being asked to move in some way by humans. When the dolphin makes a noticeable movement, the trainer makes a sound and feeds the dolphin simultaneously. When repeating this, the dolphin associates the sound with a specific action they have made and the food with it. In other words, they learn that they will be fed if they make that move, that sound is their cue, etc.

In behavior analysis, which is a branch of behaviorism, this is called “positive reinforcement.” When a behavior is followed by something pleasurable, the animal increases the frequency of that behavior. The opposite is “positive punishment.” If an animal is continually exposed to unpleasant experiences when it engages in a specific behavior, it will gradually cease to engage in that behavior.

Although operant conditioning was not discovered or established as an animal training method, Karen applied it to dolphins that humans could not punish by using “positive reinforcement” as a training method.

Karen Pryor was not originally a professional animal trainer. Karen’s ex-husband, Tap Pryor, built the Oceanic Institute, a marine animal research facility, and Sea Life Park, a recreational facility for the public, in Hawaii in 1964. And it seems that Karen was eventually sent out as a dolphin trainer.

Meanwhile, Bateson had been working as an associate director at the institute in the Atlantic Virgin Islands since 1963, at the invitation of John C. Lilly, a renowned researcher on the “language” of dolphins. Lilly seemed to respect Bateson, but Bateson said something about Lilly’s institute that the source of the funds was questionable. However, Lilly’s goal of “talking” with dolphins and Bateson’s interest in nonverbal animal communication may have been misdirected.

The Pryors were then “given” Bateson by Lilly to work at the institute in Hawaii. Bateson was associate director of the institute from 1965 to 1972. Incidentally, Bateson’s consistent interest at the time was in octopuses rather than dolphins. Bateson kept some octopuses in his room in both the Virgin Islands and Hawaii to study its communication.

Karen said the facility’s operation has been on track since its opening, but everything has been going so well that she has gradually fallen into a rut. She wanted to do something new. So, first, she decided to reinforce a different performance at each show in an individual rough-toothed dolphin named “Maria.” In other words, she decided not to give reinforcement (sound and food) to the same performance as the previous show but to give it to a different performance than the last show. Maria then quickly learned and put it into practice. She understood and practiced that each show required a different performance. But the repertoire of enhanced performances is also limited. Therefore, Karen and her colleagues decided not to give reinforcements to the performances she had shown so far. After one or two disappointing shows, Maria solved the problem. Suddenly, she performed a series of moves that no one had ever seen before. Trainers and the audience were amazed. Karen and others immediately reported this to Bateson. Bateson was also excited and observed it from the audience the following day. Maria had also performed many times in a way she had never shown before.

In Bateson’s view, Maria has learned that “only movements that have not been previously reinforced will be reinforced.” More to the point, she has become “creative,” which is a phenomenon that behaviorism cannot explain.

Let’s organize Maria’s learning process and its levels.

- Learning that it will be fed when it makes specific movements.

- Learning that it will be fed when it makes a different move from when it was fed.

- Learning that it will be fed if it makes a move it has never made before.

Behaviorism is a kind of ideology and scientific attitude that holds that the mind of a newborn organism is “tabula rasa,” or a blank slate and that all actions taken by the organism are learned from birth. This behaviorism can only account for, at most, 1 or 2 in the above example; it does not envision learning at the level of 3 at all. Bateson was critical of behaviorism, which was a powerful force at the time because it assumed only low-order learning. And the show put on by Karen and others was the very embodiment of Bateson’s criticism of behaviorism.

Bateson suggested that Karen and others conduct this as a rigorous experiment. So, with the help of the University of Hawaii and the Navy, Karen and her colleagues decided to arrange video and audio measurement equipment, hire a few more staff members and camera operators, and conduct the experiment in an aquarium in the laboratory rather than in front of guests.

Of course, Maria, who had already learned to “demonstrate creativity,” could not be used in the experiment. Therefore, they decided to use a rough-teethed dolphin named “Hou.” When the investigation began, Hou was quite different from Maria. Hou was much more docile than Maria, showed fewer signs of frustration, and was easily demotivated if not given reinforcement. So the trainers had to break the “rules” several times. In other words, they had to feed the dolphin several times, even when they should not have done so, not to lose the dolphin’s trust and make sure Hou’s motivation doesn’t go to zero. And Hou continued to perform as she had shown before until the 14th attempt. But before the 15th trial began, Hou showed evident excitement.

As soon as the trial began, she could perform a move she had never shown before. Finally, like Maria, Hou also gained insight into the “context of context,” that is, “only movements that have not been reinforced before will be reinforced,” and she put it into practice.

Hou continues to do the act she has already shown.

From LADS before the WIND DIARY OF A DOLPHIN TRAINER. Karen Pryor.

The dolphin who finally showed “creativity” after the fifteenth trial, which Bateson describes in his articles “Double Bind, 1969” and Mind and Nature, is not Maria but Hou. Even among dolphins of the same species, there is much variation in “intuition” in learning.

Karen et al. summarized the results of their experiments in a paper entitled “The creative porpoise: training for novel behavior.” They submitted it to the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, and the article received a great response.

We can read the paper on the following website.

In the paper, Bateson’s name and the term “context marker” created by Bateson are visible.

Let’s look at this experiment from an abduction perspective. There is no way to deny that Maria and Hou had some insight into what was going on, and I will try to express that process in language:

Surprisingly, the last time I performed a routine that got me fed, I still did not get fed.

However, if a different performance is required from the last time, it is natural that the same performance as the last time will not get me fed.

Therefore, a different performance from the previous one is required.

This is the kind of abduction that took place. This is the transition from 1 to 2 in the learning process described in 1-3 above.

And next:

Surprisingly, if I perform differently than I did last time, I should get fed, but I don’t.

However, if I am expected to show not merely a different performance but a performance that I have never done before, then it is natural that I will not get fed if I perform differently from the last time.

Therefore, I am required to give a performance that I have never given before.

This is the leap from 2 to 3 learning. Hou showed excitement before the 15th trial, indicating that she was excited because she had insight into why she had not received the food before and how she could get it. This was indeed an abduction.

Of course, these are not mere “trial and error.” In E. L. Thorndike’s experiments with trial and error in animals, the animals are “calculated” to encounter patterns that yield reinforcement as they move about. There is no need for the animal to have insight into anything.

There is a difference between trying various methods without thinking, as in “throw enough mud at the wall, some of it will stick,” accidentally obtaining a reinforcement in the process, and gaining insight into something in the process trial-and-error and achieving a dramatic result. Only in the latter case can we say that we are doing abduction correctly.

Japanese marten in this video seems to be a true “trial and error” process.

Karen does not believe that dolphins are the only particularly smart animals, as some do. Karen herself later confirmed the same thing with pigeons through experiments, and she writes that horses also learn this way. She also notes that Westerners quickly assign an “order of smartness” to animals, but such a question is nonsense.

After Karen experimented with How, she recalled a squirrel that used to visit her backyard when she was a child. Karen’s father had hung bird feeders for small birds on tree branches in the backyard. The feeder was suspended by a cord too thin for squirrels to climb down through so that they could not eat the food, and its roof was even steeper. One day, a squirrel came. The squirrel jumped from the branch to the feeder but fell off because of the roof’s steepness. After repeating the process three times, the squirrel climbed back up the tree and stared at the feeder for a while. The squirrel then moved to the branch on which it was hanging instead of jumping on the feeder, chewed and cut the string, and dropped the feeder itself to the ground. The squirrel then jumped down on top of the food strewn on the ground and ate it with gusto.

This squirrel would not have been able to obtain food simply by trial and error, and it had an insight into something, and it did indeed perform an abduction in that sense. But what is distinctly different from Maria and Hou is that this squirrel provided insight into “physical structure,” while Maria and Hou did not.

Maria and Hou did not gain insight into the physical structures inside and outside the tank to be able to feed. If anything has changed for them, they no longer receive food when they move to conditions that previously allowed them to obtain food. Bateson emphasizes that in the world of life and information, the “absence” of something can be important information. For Maria and Hou, the “absence” of sound and food was indeed an essential signal of a change in context.

Squirrel got what he wanted through insight into the feeder, branch, string, and other physical structures that come into view and their relationships. In other words, what is “in” the field of vision is the material of insight. On the other hand, Maria and Hou saw something “not coming,” which gave them insight into the context rather than the physical structure. We can see that there are many patterns and levels of abduction.

Incidentally, and this is something that Karen did not mention in her paper and Bateson did not write in his book, there was a curious incident regarding Maria and Hou afterward.

This Hou was still young and not yet an adult when the experiment was conducted, but later she grew up to be almost the same size as Maria, and the two became very similar in appearance. On one occasion, Maria and Hou were switched without realizing it, and the show began. In other words, Maria was suddenly asked to perform in the performance that Hou had reinforced, and conversely, Hou was asked to serve in the performance that Maria had reinforced. Maria had never been reinforced in that performance, and neither had Hou. Naturally, each dolphin was confused, but they eventually understood the required performance and did it during the show. After the show, Karen and her colleagues realized that the two dolphins had been switched.

Karen writes that she can no longer explain this event, and she says that this is not possible with other dolphins. It seems that Maria and Hou have become incredibly “intuitive” dolphins. There appears to be a relationship between creativity, good intuition, the ability to perceive, and abduction.

As I read Karen Pryor’s books, it is interesting that while it is fundamentally based on behaviorism, it deviates from it in places. For example, in Don’t shoot the dog! she writes the following.

Bringing behavior under stimulus control often gives rise to an interesting phenomenon I call the “prelearning dip.” You have shaped a behavior, and now you are bringing it under stimulus control. But just as the subject seems to be showing signs of responding to the stimulus, it suddenly not only stops responding to the stimulus, it stops responding altogether. It acts as if it has never heard of the thing you have shaped it to do.

This can be most discouraging for the trainer. Here you have cleverly taught a chicken to dance, and now you want it do dance only when you raise your right hand. The chicken looks at your hand, but it doesn’t dance. Or it may stand still when you give the signal and then dance furiously when the signal is not present.

…After that, however, if you persist, illumination strikes: Suddenly, from total failure, the subject leaps to responding very well indeed – you raise your hand, the chicken dances. The behavior is under stimulus control.

What is going on, in my opinion, is that at first the subject is learning the cue without really being aware of doing so; the trainer sees only a heartening tendency toward slowly increasing correct performance. But then the subject notices the cue, and becomes aware that the signal has something to do with whether it gets reinforced. At that point it attends to the signal rather than offering the behavior. Of course it gives no response and goes unreinforced. When, by coincidence or the trainer’s perseverance, it does once again offer the behavior in the presence of the cue, and it does get reinforced, the subject “gets the picture.” From then on, it “knows” what the cue means and responds correctly and with confidence.

I realize I am throwing a lot of words around here, such as “aware” and “knows,” referring to what is going on in the subject’s head, which most psychologists do not like to see applied to animals. Also, it’s true that sometimes, in training an animal, the level of correct response gradually increases without any big events occurring; it would be hard to say at what point, if ever, the animal becomes consciously aware of what it is doing. But when a prelearning dip does occur, I think it is a sign of a shift in awareness, no matter what species is involved. I have seen in the data of University of Hawaii researcher Michael Walker clear-cut prelearning dips (and consequently some kind of awareness shift) during sensory-discrimination experiments with tuna, one of the more intelligent sorts of fishes, but after all, merely a fish.

For the subject, the prelearning dip can be a very frustrating time. We all know how upsetting it is to struggle with something we half-understand (math concepts are a common example), knowing only that we don’t really understand it. Often the subject feels so frustrated that it exhibits anger and aggression. The child bursts into tears and stabs the math book with a pencil. Dolphins breach repeatedly, slapping their bodies against the surface of the water with a crash. Horses switch their tails and want to kick. Dogs growl. Dr.Walker found that if, during the training of stimulus recognition, he let his tuna make mistakes and go unreinforced for more than forty-five seconds at a time, they got so upset, they jumped out of the tank.

I have come to call this the “prelearning temper tantrum.” It seems to me that the subject has the tantrum because what it has always thought to be true turns out suddenly not to be true; and there’s no clear reason why…yet. In humans prelearning temper tantrums often seem to take place when long-held beliefs are challenged and the subject knows deep inside that there is some truth to the new information. …However, I have come to regard the prelearning tantrum as a strong indicator that real learning is actually finally about to take place. If you stand back and let it pass over, like a rainstorm, there may be rainbows on the other side.

From Don’t shoot the Dog! The new art of teaching and training. Karen Pryor.

As Karen writes, behaviorism and behavior analysis basically do not explain animal psychology in terms of “notice,” “know,” “aware,” or “understand.” But Karen deviates from that very point. This is probably because she has seen so many cases where she has had to consider that the animal is aware or understands something. This seems to be precisely the influence of Bateson, Maria and Hou, whom she has witnessed firsthand.

Karen’s description of “prelearning dip” and tantrums with it does not entirely overlap with abduction, but it seems to be the same in the sense that the frustration occurs before the insight.

As a side note, “clicker training” was established by Karen as a method for training dolphins and then applied to training dogs and other pets and spread to many countries. This method of training dolphins to perform without punishment, which Karen has established, can be applied to other animals. The animals are not punished, but they also enjoy the playful nature of the training. Many trainers who have learned and adopted this method have found that the animals are more willing to participate in the training. Thanks to this training method introduced by Karen, the number of pets that their masters punish for performing tricks may have been significantly reduced. (Incidentally, it is said that the effect is the same if the cue is not a clicker but a voice. However, a clicker that can produce a sound by simply pressing a button on the hand is by far the easiest way to signal.)

Karen Pryor discusses clicker training. She talks about how it came about in the process of training dolphins at Sea Life Park.

The explanation of the training method and how the dog learns step by step is very easy to understand.

◆ General remarks

I have explained metaphor, analogy, induction, deduction, and abduction using Kobo-chan as an example. I believe I have now explained each of the basic patterns of thought.

Thinking about thought patterns can be called “meta-thinking.” This kind of work may be considered “philosophical.” However, Masashi Ueda, the author of Kobo-chan, majored in philosophy at university. Then, it is natural that Ueda’s work should be “philosophical” to some extent. This makes it possible to organize each thought pattern using Kobo-chan as an example.

I hope these considerations will help those who wonder what each thought pattern is.

5.13 2022

◯References

Yuji Yonemori. Abduction Hypothesis and Logic of Discovery アブダクション 仮説と発見の論理. Keisou Shobou. 2007.

Bateson, Gregory. 2000. Steps to an ecology of mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pryor, Karen. LADS before the WIND DIARY OF A DOLPHIN TRAINER. Sunshine Books, Inc, 2000.

◯Reference website

◆ About Hybrid vigor

90 Years Ago : The Beginning of Hybrid Maize

Commentary by James F. Crow

Inbreeding and Outbreeding Their genetic and sociological significance

Book co-authored by E. M. East and D. F. Jones

Actual breeding methods 品種育成法の実際

A site that explains various breeding methods.(Japanese)

Innovation of “hybrid corn”(1) 「ハイブリッド・コーン」というイノベーション(1)

A site that explains Shull’s “hybrid vigor” from the perspective of innovation.(Japanese)

Kametaro Toyama and the “breeding” of silkworms in the sericulture industry during the Meiji period 外山亀太郎と明治期の蚕糸業における蚕の「種類改良」

This site describes Kametaro Toyama of Japan, who had actually put hybrid vigor into practical use in sericulture earlier than Shull and East. It is interesting to know that there was a controversy over whether selection or hybridization was used in the improvement of silkworm breeds. (Japanese)

Cocoon Size and Cocoon Yarn Length – Dr. Kametaro Toyama – 繭の大きさと繭糸の長さ-外山亀太郎先生-

This is an easy-to-understand site about hybrid vigor in sericulture. (Japanese)

Yoichi Kakizaki, the First to Create Hybrid Varieties of Vegetables 世界ではじめて野菜のハイブリッド品種をつくった柿崎洋一

About Yoichi Kakizaki, who created the first F1 variety of eggplant.(Japanese)

Kenkichi Sakai, Creator of the “Kogane Sengan” Sweet Potato Breed – Kenkichi Sakai’s Fierce Breeding. サツマイモ品種「コガネセンガン」生みの親 ~坂井健吉のモーレツ育種~

Kogane Sengan – A Miracle Borne of Dr. Kenkichi Sakai’s Breeding Spirit‐ コガネセンガン-坂井健吉博士の“育種魂”が産んだ奇跡-

The articles describes Kenkichi Sakai, who created the “Kogane-sengan,” a large variety of sweet potato mainly used to make sweet potato shochu (distilled spirits), through hybridization. (Japanese)

Kogane Sengan continues to produce Kagoshima’s specialties. New possibilities are now available with the perfection of a super-specialty sweet with a ” best before 15 minutes” 鹿児島の特産品を生み続ける「コガネセンガン」 “賞味期限15分”の超こだわりスイーツの完成で新たな可能性も

HELLO MINAMIKAZE ハロー南風

Kogane Sengan was originally produced for starch processing, but it is also used in sweets because of its good taste. A café in Kagoshima that serves sweets made from Kogane Sengan has erected a monument in honor of Kenkichi Sakai on its premises.

The Coming Era of F1 Potatoes 迫りくるF1バレイショの時代

Hybrid vigor is also being studied in potato cultivation. By cultivating potatoes from seed, which has never been considered, the production efficiency is about 100 times higher than cultivation from seed potatoes. If the potatoes become infected with a disease, the seed potatoes themselves become a source of infection, making management difficult, but the seeds do not have this problem, so it is said to significantly reduce costs and labor. (Japanese)

Development of the Wasabi F1 hybrid Variety “Fuji Midori” ワサビ一代雑種(F1)品種「ふじみどり」の開発

The article describes the world’s first wasabi F1 hybrid. (Japanese)

What kind of varieties are F1 varieties? F1品種って、どんな品種

Seed company Tohoku explains about F1 seeds on this page. It is easy to understand the difference between Open pollinated seeds. (Japanese)

What kind of pork is Sangenton? A complete explanation of the brand name pork, from delicious recipes to restaurant recommendations! 三元豚とはどんな豚?銘柄豚のご紹介、美味しいレシピから、おすすめレストランまで完全解説!

This page from food processing manufacturer Saiboku explains Sangenton (Three-crossbred pig). It is highly documented with vigor covering aspects of genetic improvement in pig farming.(Japanese)

The Wonderful Effects of Hybrid Vigor Not Measured by Genomics ゲノムでは測れない雑種強勢の素晴らしい効果

It seems that hybrid vigor has been adopted in Wagyu cattle.(Japanese)

Dairy Caws Rotation Breeding in the U.S. 米国における乳用牛の輪番交配の取り組み

This article describes the hybrid breeding of dairy cows in the United States. Hybrid dairy cows produce a few percent less milk than Holsteins, but they have a lower stillbirth rate, are healthier, and live longer, resulting in a higher profit margin per cow. (Japanese)

Heavy breed horse improvement services 重種馬の改良業務

About the Sires of the Top Horses. Tracking the Patriarchs of the Top Horses – Aono Black’s Sire Line Vol. 1 ばん馬の種雄馬について トップホースの父系を追う~アオノブラックのサイアーライン Vol.1~

What is the pedigree of “Ban’ei horse”, which is different from Thoroughbreds? How to Enjoy Ban’ei Horse Racing More サラブレッドとは違う「ばん馬」の血統って?【プロに聞くばんえい競馬をもっと楽しむ方法】

It seems that almost all of the horses that participate in Ban’ei Horse Racing are from hybrid vigor.(Japanese)

Hybrid Vigor in Horses: Outcrossing Explained

Hybrid vigor is also being introduced in American Quarter Horses.

Patent Introduction: Method of Creating a New Breed of Cockel 特許紹介 トリガイの新品種の作出方法

Heterosis in the Cockle Fulvia mutica in a Crossbreeding Experiment among Inbred Linesトリガイ近交系交雑に見られた雑種強勢

Hybrid vigor seems to have been adopted in cultured cockles as well. (Japanese)

The Trajectory and Future of Rice Breeding in Japan – Rice Breeding in Topics – 日本のイネ育種の軌跡と行方-トピックスで綴るイネ品種改良-

The question of whether rice hybrid vigor should be adopted in Japan is being considered. (Japanese)

Molecular Biology and Prospects for Plant Hybrid Vigor Toward Efficient Yield Enhancement 植物の雑種強勢の分子生物学的な研究と展望 効率的な収量増産に向けて

DNA methylation is important for hybrid vigor -Expectations for the effect of breeding high-yielding vegetable varieties DNAのメチル化が雑種強勢に重要であることを発見-収量性に優れた野菜の品種育成の効果に期待-

Five Important Genes Sufficient for Biomass Hybrid Vigor of Sorghum F1 Variety “Tentaka” Revealed ソルガムF1品種「天高」のバイオマス雑種強勢に必要十分な5重要遺伝子が明らかに

Microbes Play Role in Corn ‘Hybrid Vigor’

The molecular mechanism that causes hybrid vigor has long been a mystery, but it seems to be on the way to being clarified in recent years.

Expansion of learning capacity elicited by interspecific hybridization 異種間交配によって学習能力が拡張することを発見~神経行動学版「トンビが鷹を生む」:子のほうが親よりも学習能力が高い

Hybrid individuals born from interspecific crosses between Taeniopygia guttata and Aidemosyne modesta are able to learn a greater variety of songs than their parents, meaning that the effect of hybrid vigor is not only seen in physical aspects such as body size and disease resistance, but also in learning ability.

◆ About Selection Limits

A theory of limits in artificial selection

Theory of Selection Limits by Alan Robertson

Alan Robertson (1920-1989)

History of population and quantitative genetics and the contribution to animal breeding (Japanese)

Study on the Selection Limit for Small Body Weight in Japanese Quai 日本ウズラの体重小方向への選抜限界

Study on the Selection Limit for Large Body Weight in Japanese Quai 日本ウズラの体重大方向への選抜限界

Examples of Selection Limits

◆ About Dolphin Abduction

The creative porpoise: training for novel behavior

Oceanic Institute

The site of the Oceanic Institute, founded by Tap Pryor and of which Gregory Bateson was associate director. Apparently it is now part of the University of Hawaii.

Sea Life Park HAWAII

The Sea Life Park site was established at the same time as the Oceanic Institute.

- SmaSurf クイック検索

※The content, text and images are prohibited to reproduce, quote or use in any way other than for correct quotation.