An attempt to explain the difference

between Conflict and Contradiction

using Shogi as an example

Contents

❖ Conflict and Contradiction

In the past, there were many “dialecticians” in Japan who would start talking about “dialectics” in the second word. But it seems that the number of dialecticians has dwindled, perhaps because of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

And those dialecticians must have been saying “contradiction-conflict” as if it were a habit. They spoke of “contradiction” and “conflict” as if they were the same thing as being okay to equate them.

In the first place, the two words describe different phenomena.

Briefly, “contradiction” describes a logical or semantic state, while “conflict” describes a psychological state.

Therefore, it is possible to be logically and semantically contradictory while at the same time being psychologically conflicted or not. On the other hand, there are times when we are psychologically conflicted but not logically or semantically contradictory.

In logic, a contradiction is “A and not A,” that is, “It is A, and it is not A simultaneously.” When a kind of “logical time” is introduced into here and becomes a cycle of “if it is A, then it is not A, and if it is not A, then it is A,” it is generally called a “paradox.”

Conflict, on the other hand, is essentially a question of “A or B.”

This is a simple but important point. Contradiction is what happens between “A” and “not A,” but conflict is what happens between “A” and “B.” (Of course, the number of choices can be more than two.)

When I try to explain the difference between “conflict” and “contradiction” more concretely, I think of bringing up proverbs, for example, but it is not a good idea. I could give various models, but it would be a waste of time to use words.

There must be a better way.

❖ Explanation of Conflict

When I played Shogi against a computer as a relaxation game, I noticed two distinct phases in Shogi where you experience conflict and contradiction.

To be more precise, there are “two alternatives” and “it seems like two alternatives, but in reality, there is no choice.” The former can be called a conflicted situation, while the latter is a contradictory situation.

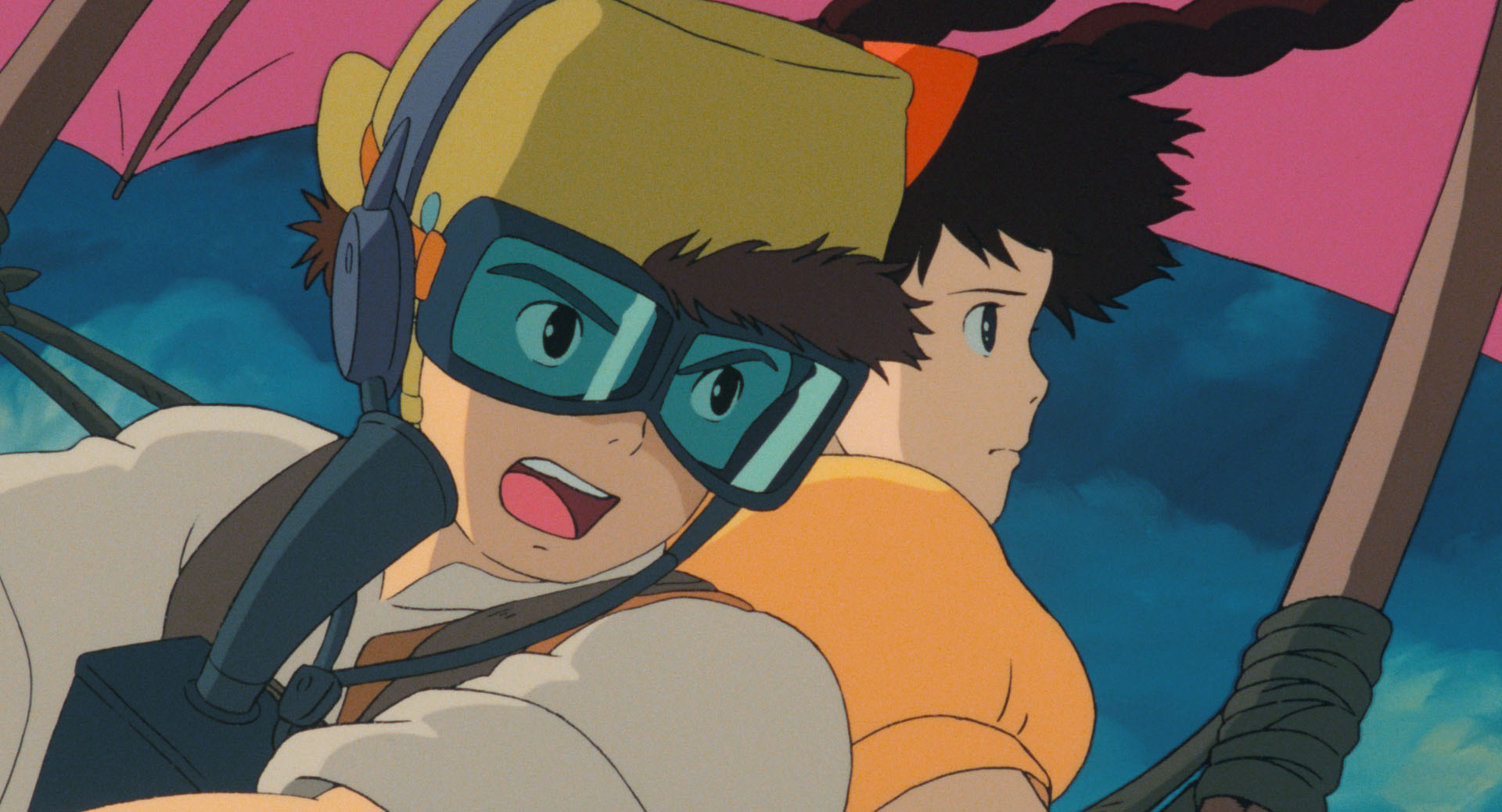

When playing Shogi, one can say that the player experiences conflict in a situation where they are subjected to the so-called “fork.”

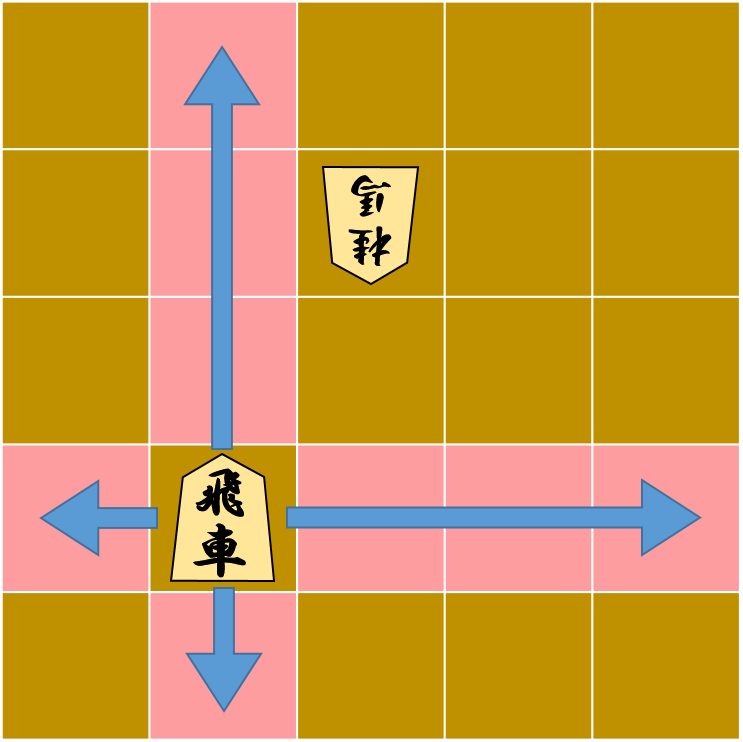

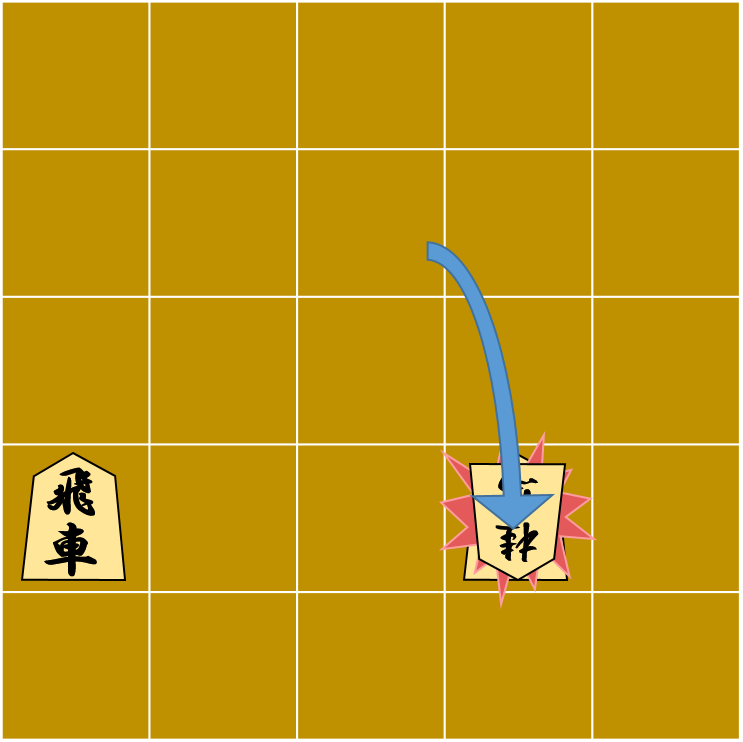

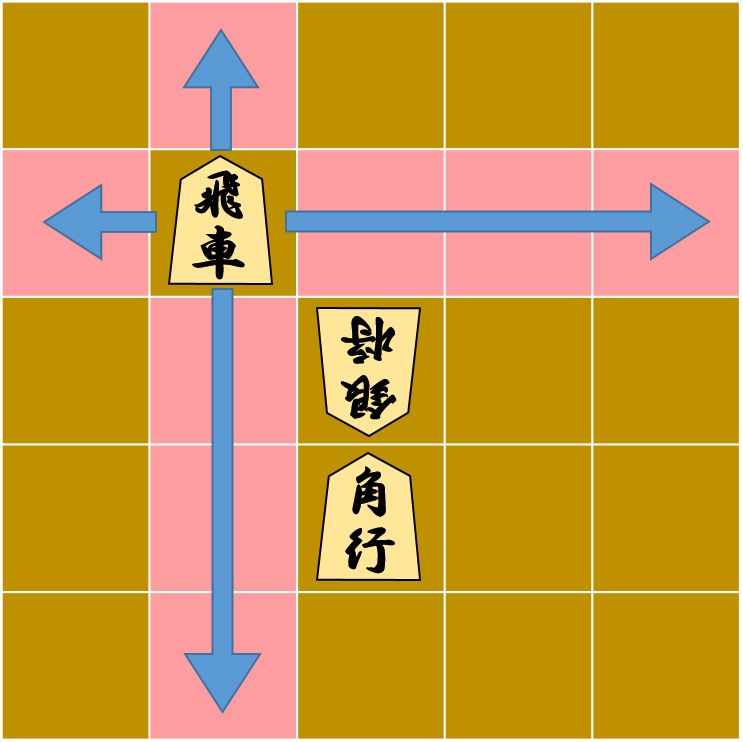

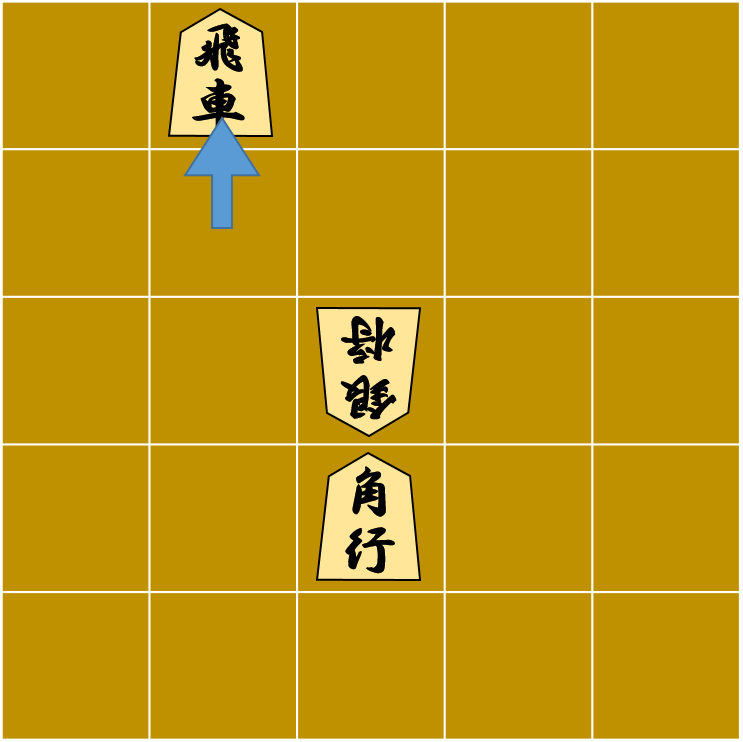

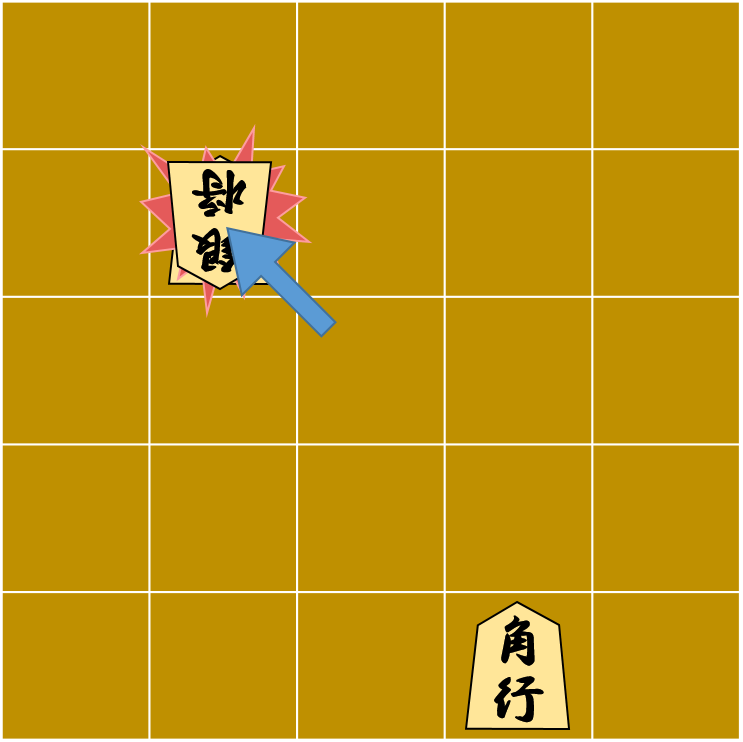

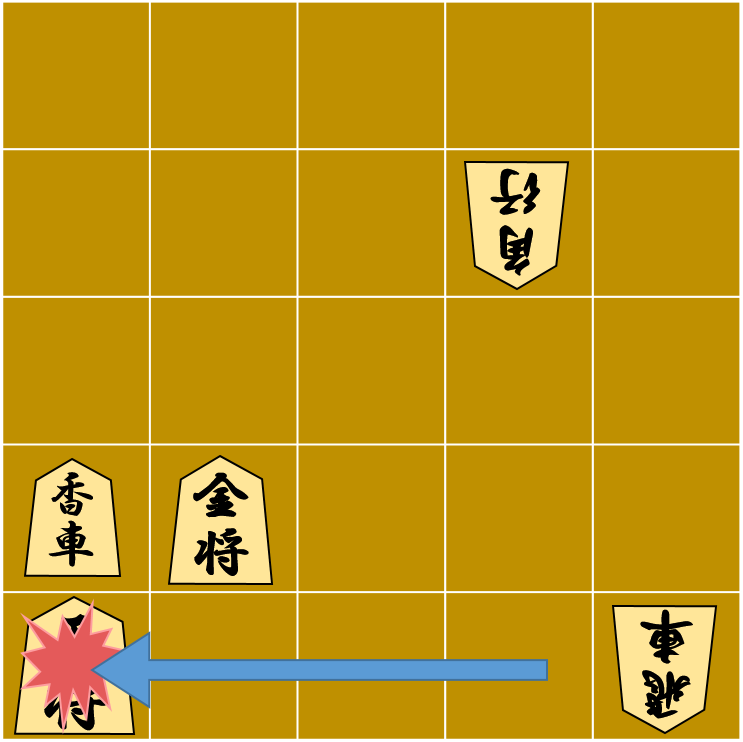

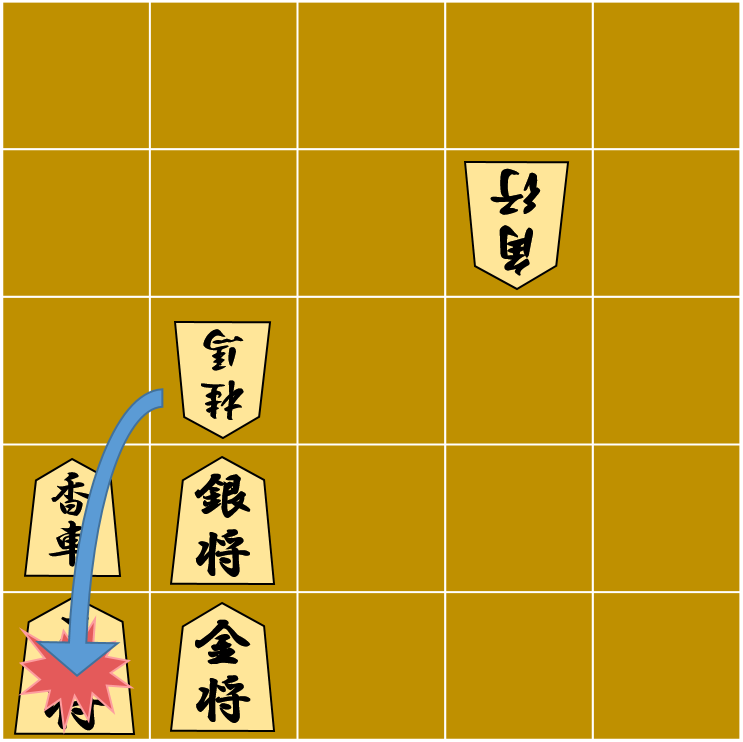

Figure 1

For example, in Figure 1, the opponent’s “Knight (keima桂馬)” piece forks against your “Rook (hisha飛車)” and “Bishop (kakugyō角行)” pieces. In this situation, Rook and Bishop are in the attack range of Knight, while Knight is neither in the attack range of Rook nor Bishop. So while Knight can attack both Rook and Bishop, neither Rook nor Bishop can take Knight. Both Rook and Bishop are called “big pieces” because they are useful pieces with a large range of movement and attack, but one of the big pieces will undoubtedly be taken in this situation.

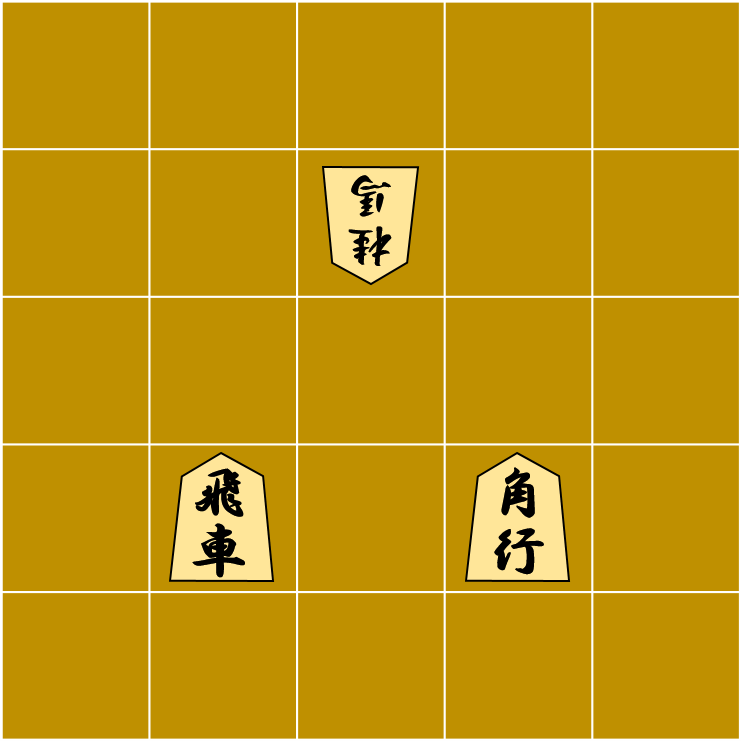

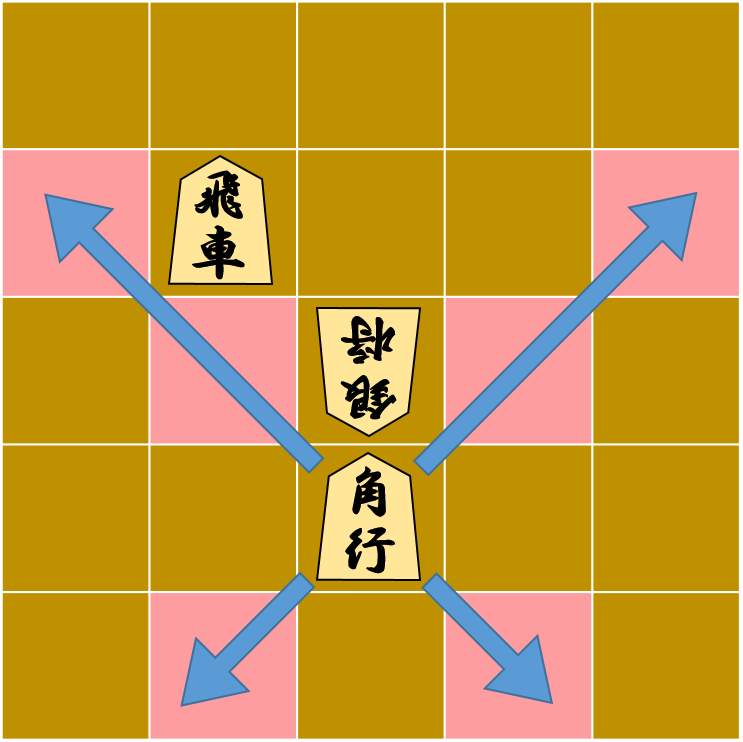

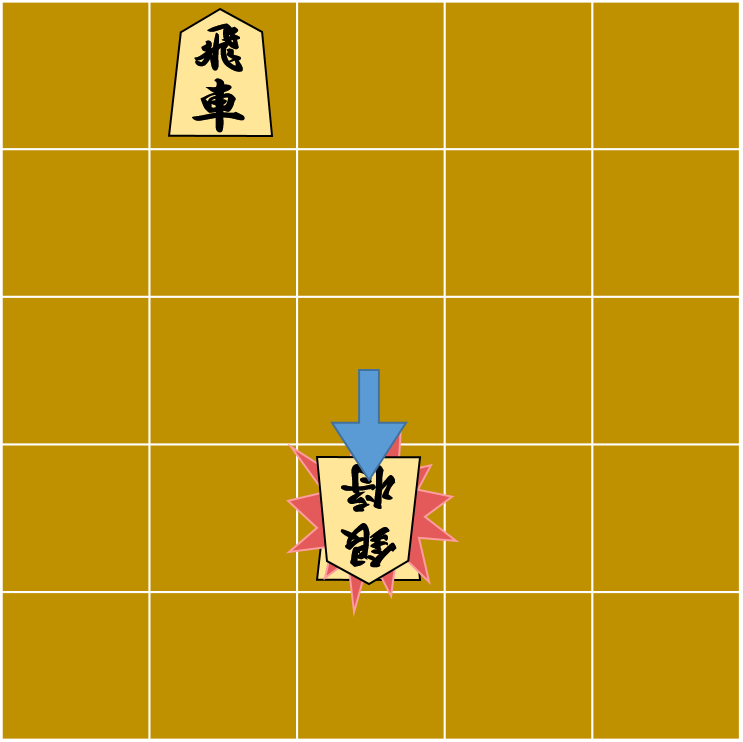

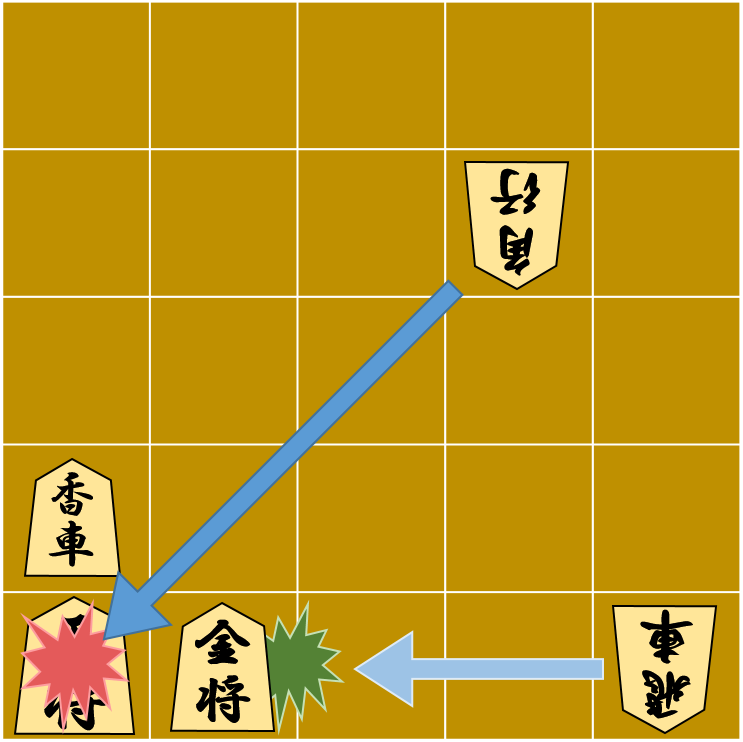

But you can decide which one you want to keep. Bishop is taken if you let Rook go; if you let Bishop go, Rook is taken. The player has to choose between Rook and Bishop. In other words, it is a situation of “two alternatives.” And the player who is forced to choose between the two has to experience conflict. (Figure 2)

Figure2

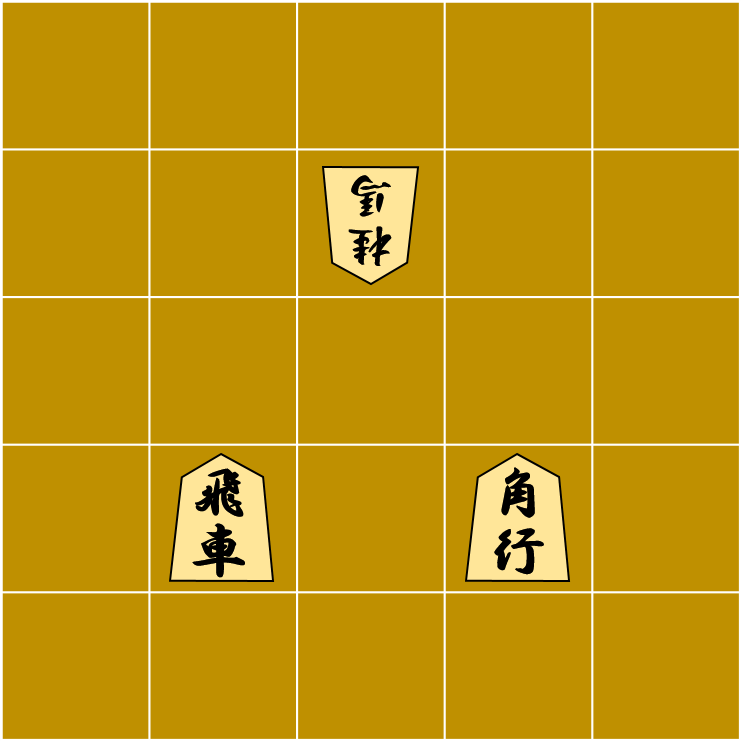

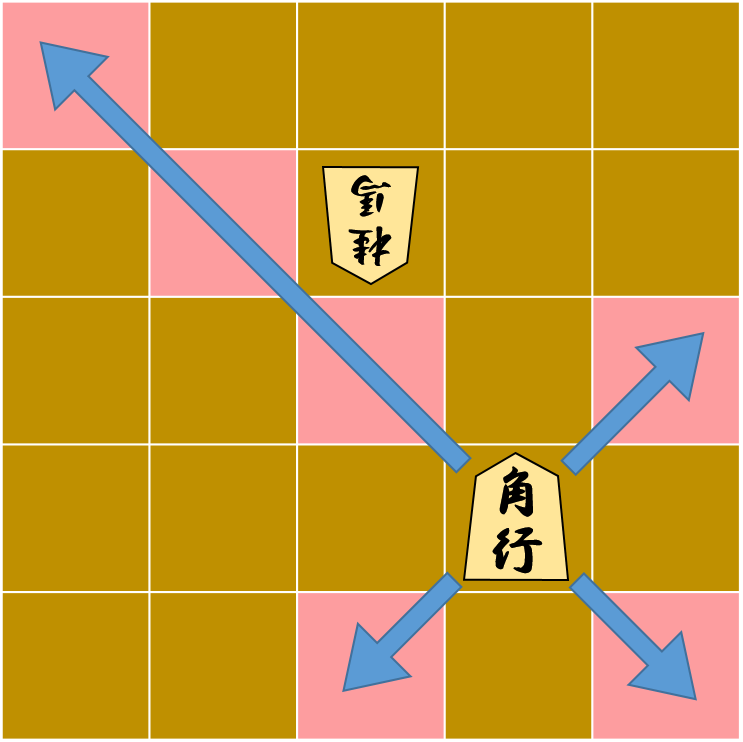

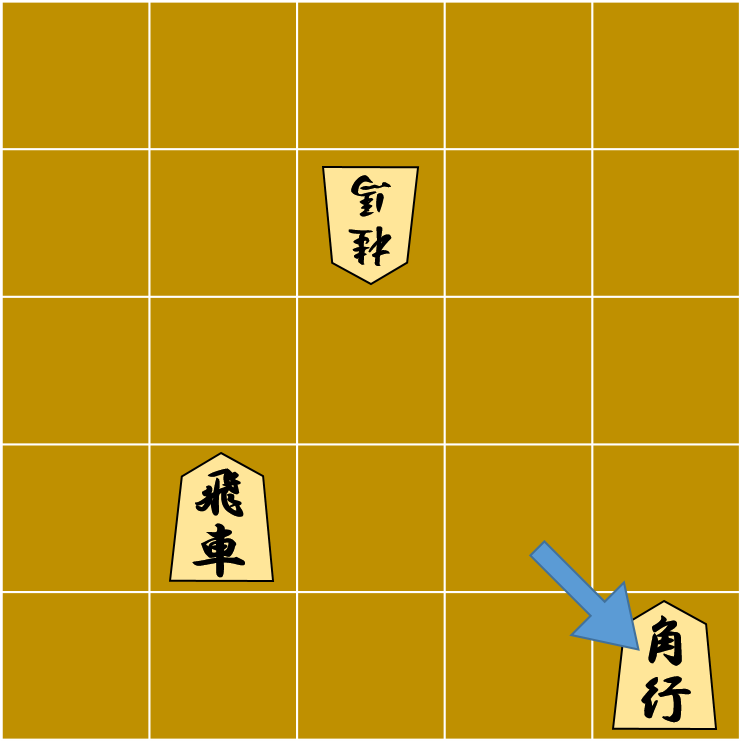

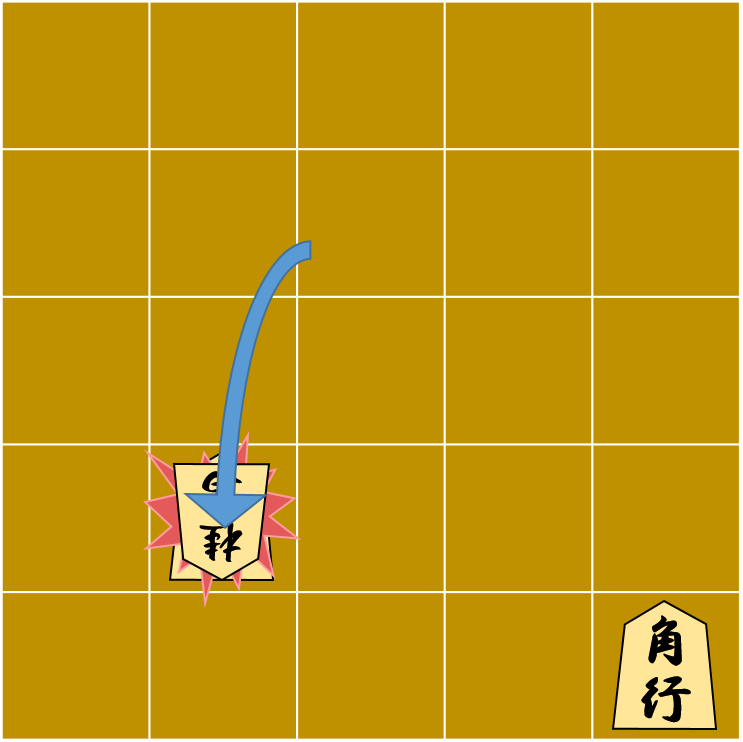

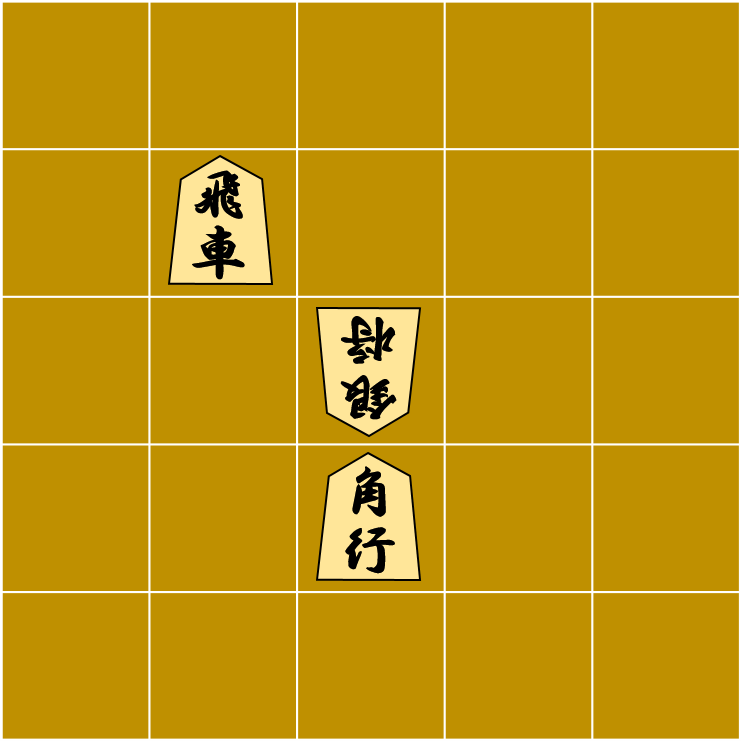

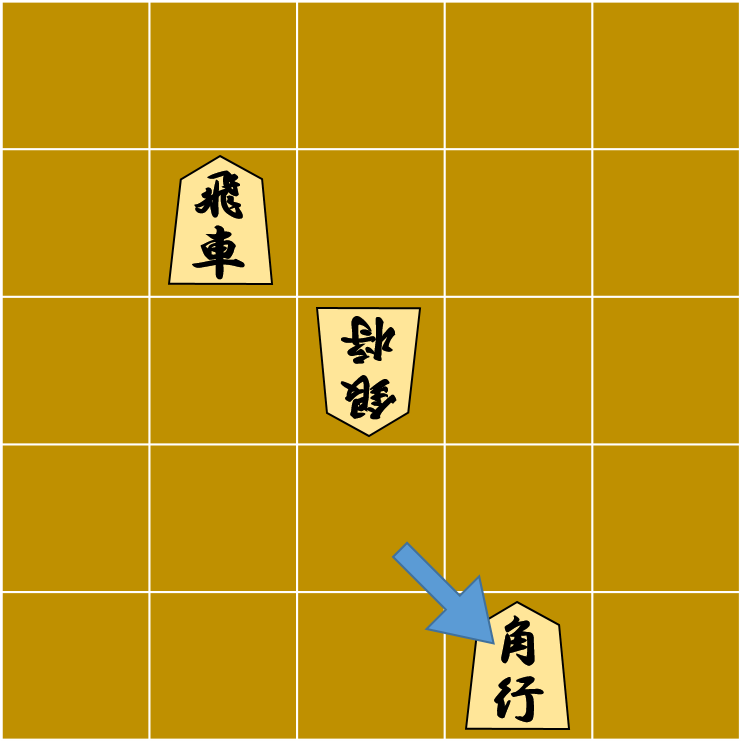

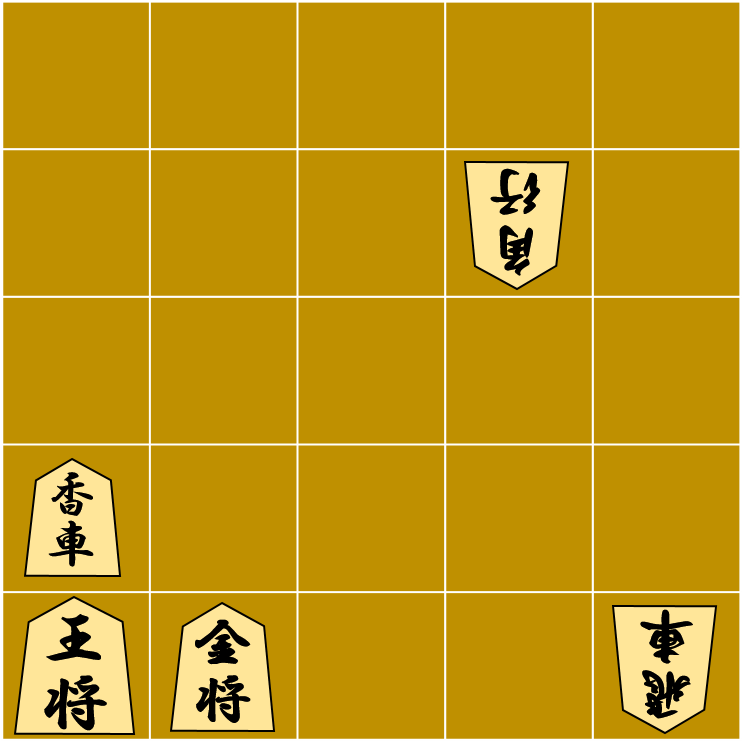

Incidentally, Figs. 3 and 4 also show the same situation. As in the previous example, Rook and Bishop are in the attack range of “Silver general (ginshō銀将),” while the Silver general is not in the attack range of either Rook or Bishop. So Silver can attack both Rook and Bishop, but Rook and Bishop can’t take Silver.

In this case, the player is still forced to the two alternatives.

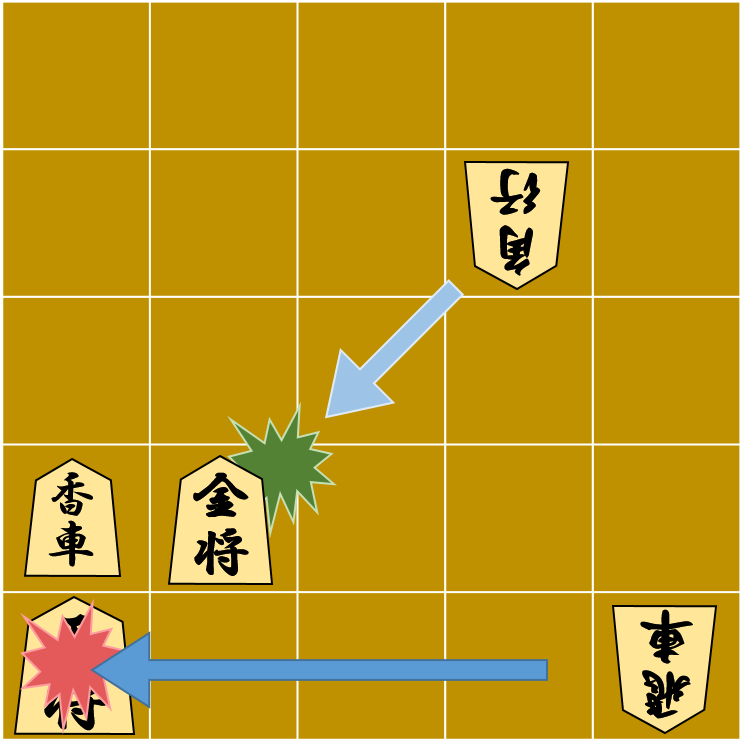

Figure3

Figure4

❖ Explanation of Ccontradiction

There are situations in Shogi where we can say that we experience contradictions.

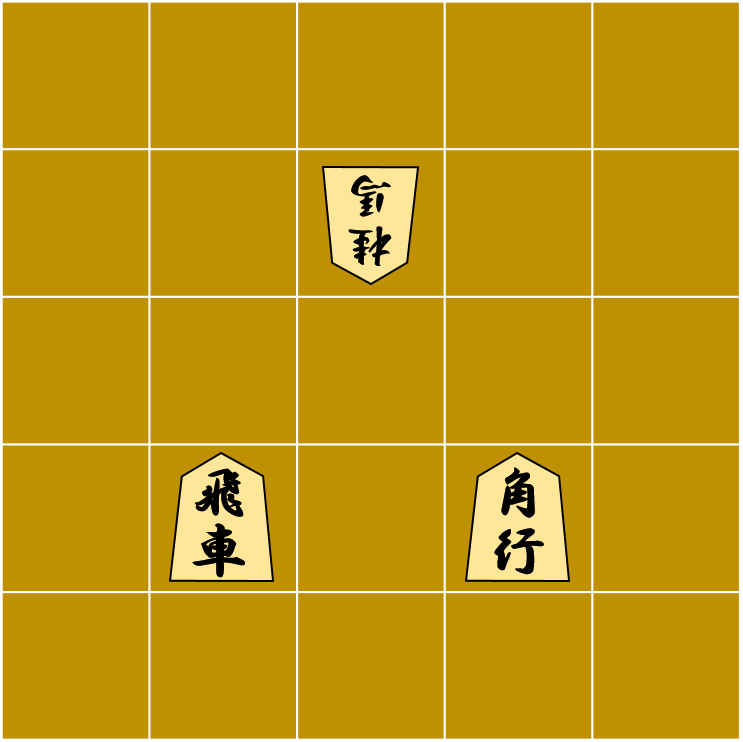

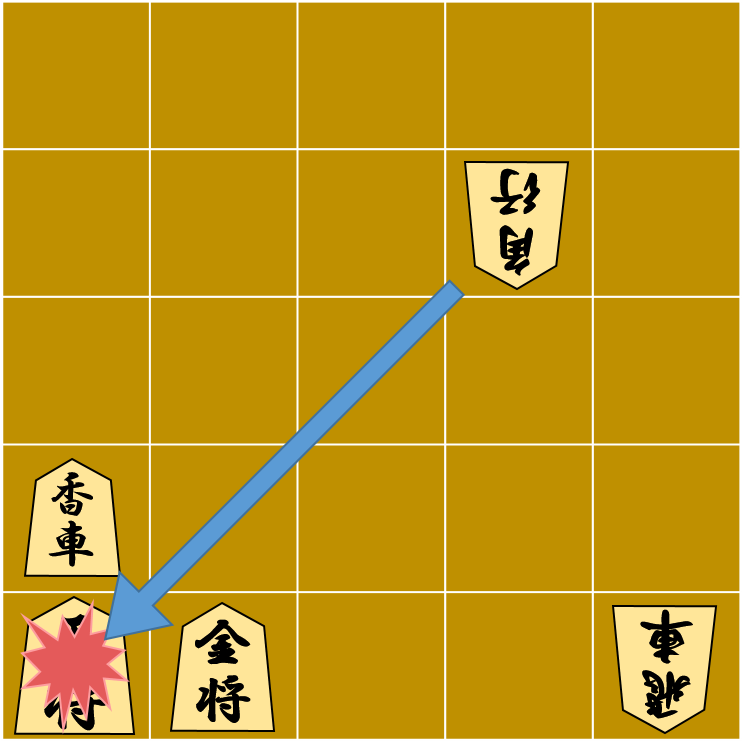

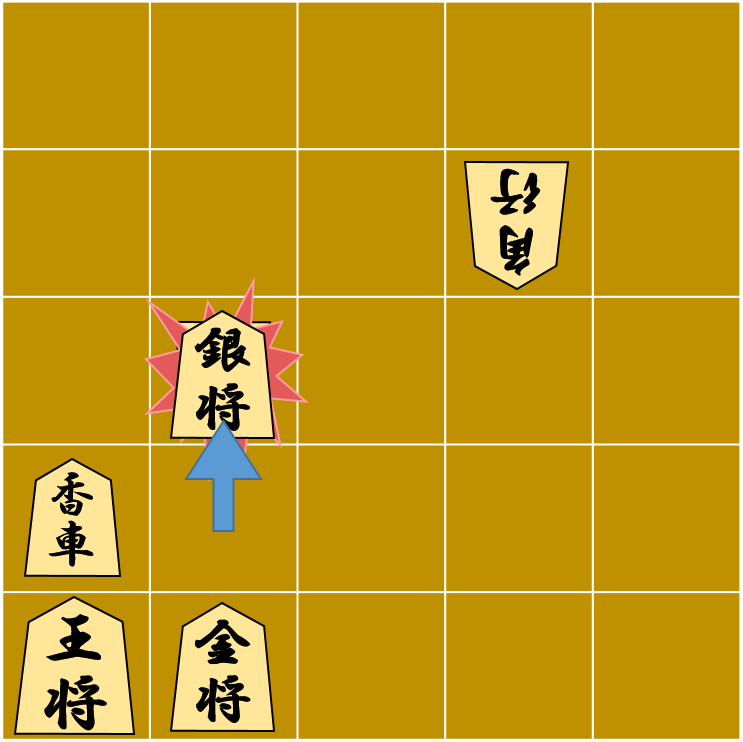

For example, this is the situation in Figure 5. In this case, the opponent’s Bishop is aiming at the “King (ōshō王将).” This is what is called a “check” situation. In Shogi, you lose if the King is taken, so you will lose if this situation continues.

Figure5

King can move one square in every direction, but King cannot move forward because there is a “Lance (kyōsha香車)” in front of him. The only place he can move is in front of the “Gold general (kinshō金将),” but even if he moves there, he is still in Bishop’s attack range. And the Lance can only go forward. So the only thing the player can do here is to move his Gold general forward one square to protect King from Bishop’s attack.

However, if you do that, the opponent’s Rook on your right will check your King.

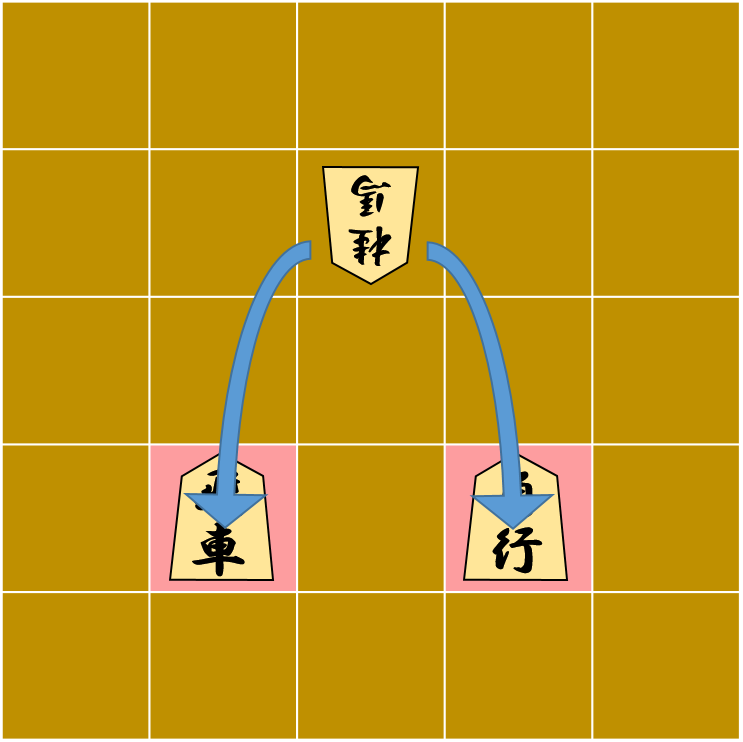

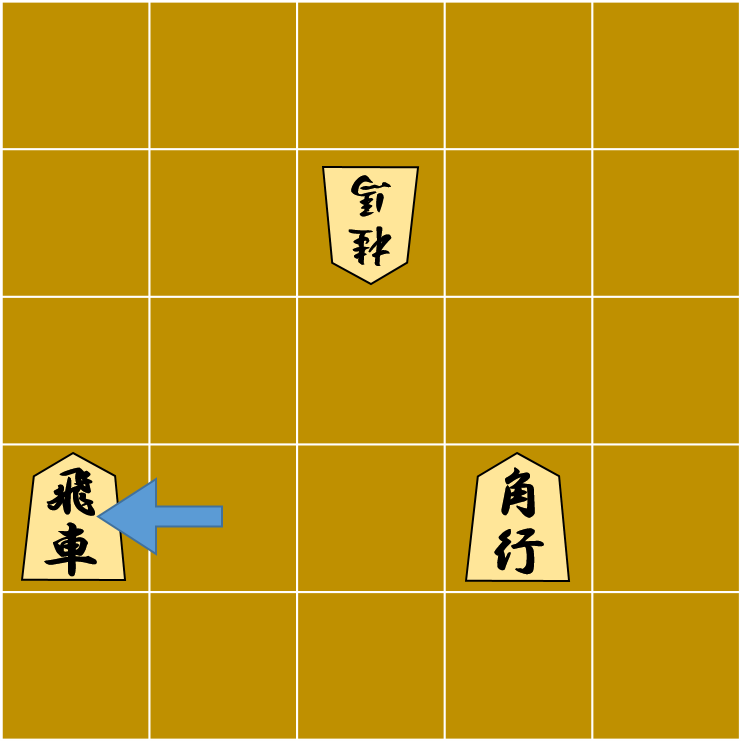

In other words, if Gold does not move, Bishop will take King, and if he moves, Rook will take King. (Figure 6) What should you do?

There is nothing you can do about it. At first glance, it looks like you have a choice about the Gold’s move, but in fact, you don’t. This is what we call a “checkmate (tsumi詰み).” (In the first place, it seems that this state violates the rule “Not leaving one’s king in check.”)

Figure6

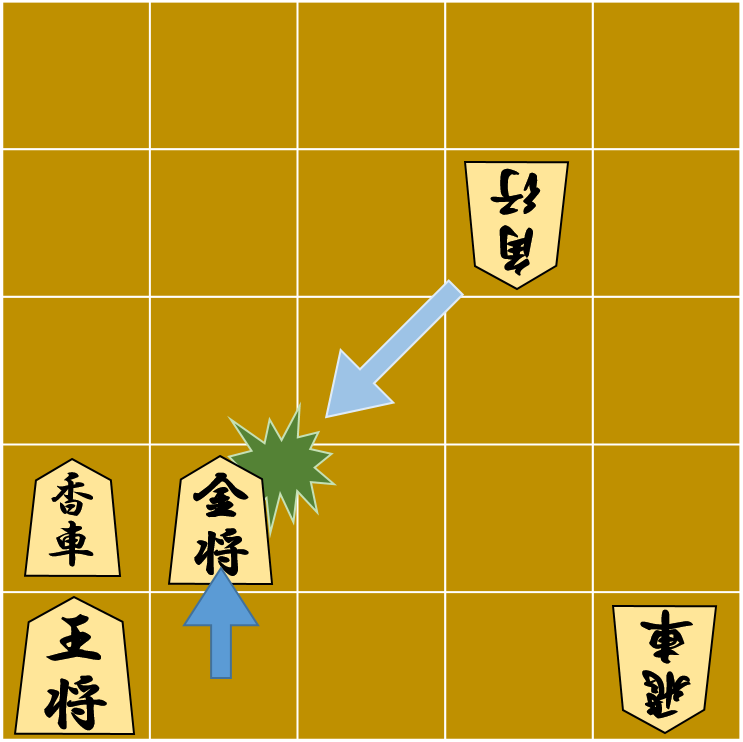

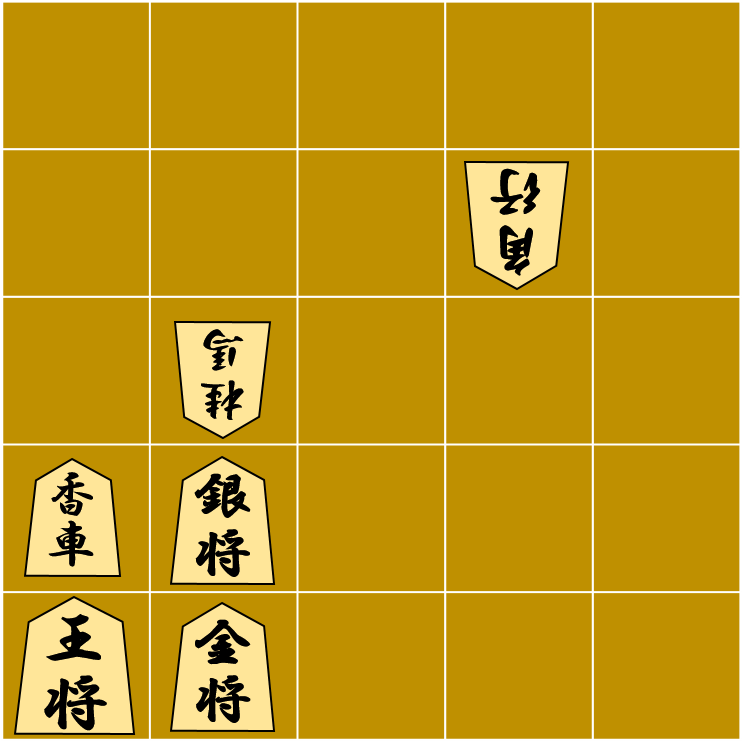

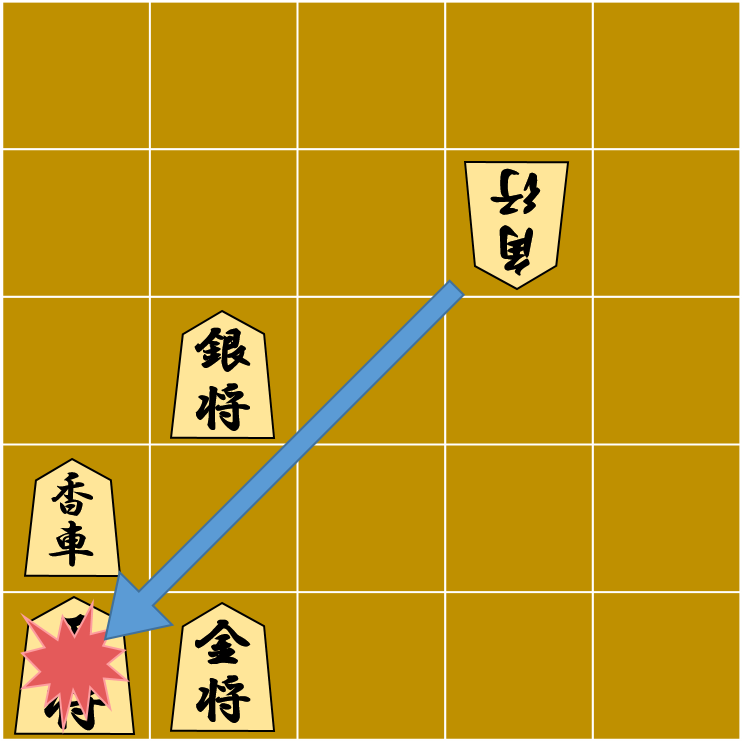

Figure7

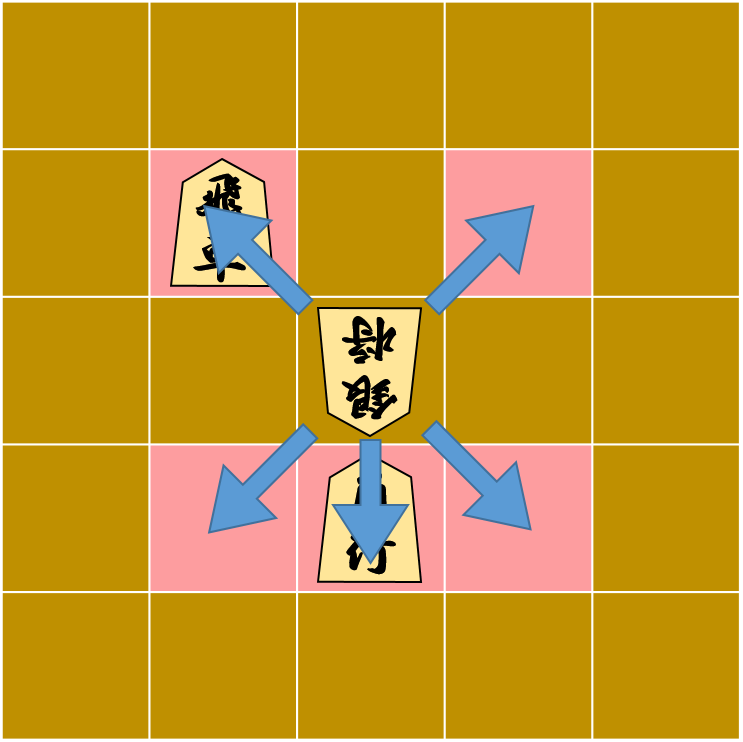

Figure 7 shows the same situation as a checkmate. In this case, the opponent’s Knight is in front of your Silver. Knight is the only piece in Shogi that can jump over other pieces, friend or foe, and your King is in the Knight’s attack range. So your King will be taken by Knight, and you will lose.

To prevent this, you can move Silver forward and take Knight, but this will open the way to attack King for the opponent’s Bishop in the upper right corner.

In other words, the Silver can’t move and can’t stay still.

This is a contradictory situation from your side.

The definition of contradiction in logic was “A and not A,” that is, “It is A, and it is not A simultaneously.”

If we apply the definition of contradiction to the situation in Figures 5 and 6, we get “can prevent an attack on King, but at the same time cannot prevent an attack on King.”

Alternatively, if we conform to the rule of “leaving check,” moving or not moving Gold, you would violate this rule. It is a matter of “dealing with the check and not dealing with the check simultaneously.”

This is clearly different from the “fork” situation. The fork is two alternatives, but there is no way to choose in this case.

I think I have been able to explain the fundamental difference between “conflict” and “contradiction” not only by words but also by the visual representation of Shogi.

❖ As an example of a Double Bind

In an actual Shogi game, when the game becomes a checkmate like this, the player admits defeat by saying, “I lost,” and can finish the game. Or, if the player realizes that the game will surely be checkmate in the next few moves, they can admit defeat and finish the game in the same way. Therefore, although the defeated player may feel frustrated, they do not feel the stress of contradiction.

Let’s make one assumption here.

First of all, let’s assume that the game cannot stop even if it turns out to be checkmated. And let’s assume that each piece has its own spirit. Furthermore, the game will be continued for a long time without being terminated. Then, what will happen to the mind in the Gold general’s piece? Will the mind remain “healthy” forever?

This hypothetical situation is similar to what Gregory Bateson calls a “double-bind” situation.

Sometimes people explain the double bind as a “conflict” situation, a situation in which there are two alternatives, but this is an apparent misunderstanding. A double bind is not a situation of two alternatives but a situation in which one is constantly under the illusion of choosing between two alternatives even though there are no choices. In other words, a situation in which one is already “checkmated.”

What is unique about Bateson’s theory for the etiology of schizophrenia is that he assumes that it is the result of “learning.” He does not attribute the etiology to deterministic factors such as heredity. Or, conversely, to non-deterministic factors such as anyone can develop this disease anytime and anywhere.

Bateson wondered if schizophrenic patients develop unique conditions because they have learned them in advance, and if so, what have they learned?

In some cases, learning leads to mental abnormalities.

There is an experiment called the “experimental neuroses” using dogs. In this experiment, dogs are shown a circle and an oval and are rewarded if they choose the circle and given an electric shock if they choose the oval. If the researcher keeps doing this, the dog will choose only circles. The dog learns that if it selects a circle, it will be rewarded, and if it selects an oval, it will be punished. And, the difference between the circle and the oval is gradually made smaller and smaller to the dog. When the difference becomes so tiny that the dog can barely tell, he loses his mental stability and develops neurotic symptoms. The dog will not know the difference and why he is being rewarded or punished, but he will be under a lot of stress because he is forced to choose.

However, the dog’s mental stability would only be disrupted by this experiment if it had learned the above beforehand. If the researcher presents a circle and an oval with little difference to a dog that has not learned, nothing will happen. Alternatively, dogs that have already learned to do so will still show no neurological symptoms if subsequent experiments are conducted in a place without “context markers” to indicate that it is a “laboratory.”

This experiment is one of the grounds of an argument for Bateson’s hypothesis that the etiology of schizophrenia is learning and experience.

This video shows that a dog was asked to distinguish between two electrical stimuli that are slightly different in frequency that were not a circle and an oval, but could no longer do so, stopped eating food on the experimental table. However, when they got off the table, they were eating normally.

Incidentally, it seems that there are contradictions in the rules of Shogi. For example, “the last judgment” in Tsume shogi.

There are various rules in games, including Shogi, and in society. But especially when the rules are in the form of “prohibitions,” i.e., “you must not ~,” contradictions can occur between multiple prohibitions. Or, when the rules are “self-referential,” contradictions can occur.

In any case, to understand contradictions, we must first distinguish them from conflicts.

I hope the above discussion will help those who wonder what the difference is between “conflict” and “contradiction.”

2021 7.4

◯Reference sites

Contradiction in Tsume-shogi: “The Last Judgment” Wikipedia (Japanese)

※The content, text, images, etc. may not be reprinted, quoted, or used in any way except for correct quotation.